The power of technology for learning and teaching

Integrating technology into your classroom can have many benefits, from easy collaboration to monitoring air quality.

Technology is ubiquitous in modern classrooms. Interactive whiteboards, computers, ipads, and VR headsets are commonplace. With these devices comes a range of software options to enhance learning, catering for different learning styles and a broad scope of activities.

Read the Term 3 edition of School News HERE

One small scale study conducted in a tertiary US context demonstrated the potential of technology to improve student engagement. The study found that student participation in class, preparation for class, attentiveness, learning and impression of the course and instructor tends to improve when technology is well utilised.

All students can benefit from technology in the classroom. Learning can become self-paced, with software options to facilitate self-directed progress. Some programs will prompt a student to practise a concept until they fully understand it, ensuring each student meets required standards. Programs can also alert teachers to students who may need extra support to understand a learning activity.

Cloud based work and file sharing systems mean students do not need to be in the same classroom to complete group work. Collaboration between different students and class groups is easily undertaken. Projects can also be enriched with the aid of technology, and students can be encouraged to incorporate rich multi-media into their work, including video, sound, animation and graphics.

With technology and connectivity an inevitable part of young people’s lives, it is important students are taught digital literacy. This can be taught in house, on a regular basis, for example each time students browse the internet to find a reliable research source, or teaching a balance between screen time and offline time. Your school may wish to engage the services of an outside provider to teach safe technology use to students. This can be extended to staff as a professional learning opportunity.

Staff may also benefit from PLD to help them make the most of technology in the classroom. Often, the company that has provided devices or software will provide training and support to ensure staff can use technology efficiently. Specialist companies can also be engaged, to teach students and staff how to use technology to study efficiently, keep notes digitally and organise files.

To find out more about emerging technology trends and how these can be used in the classroom, School News spoke to Simon Port, Regional VP Sales, UKI & ANZ, at Promethean.

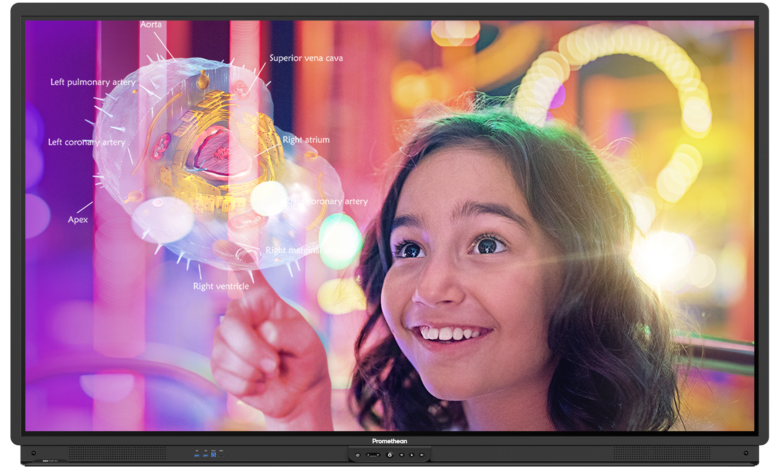

Mr Port said modern technology solutions represent a new frontier in the classroom. “Interactive devices, including front-of-class displays, change how teachers can present content and engage with their students.

“The potential of interactive devices can be seen in popular teaching methods, including gamification and ‘flipping the classroom’. As digital natives working with a central interactive device, students can take different roles including becoming a presenter, creator, or even delivering a ‘student as teacher’ session,” Mr Port said.

“Software can assist teachers in the classroom, and support them with wider school tasks and processes. Repeat administrative tasks such as taking the register or uploading lesson content to school management software are made easier with effective technology, especially cloud-connected devices which enable seamless sharing and collaboration.

“For students, the benefits of carefully chosen software are plentiful. Individual demands and learning styles can be specifically catered to, improving engagement and outcomes. Access to software can also build students’ confidence, with the ability for them to demonstrate their knowledge in different ways.”

“A key benefit of interactive front-of-class displays is simply that they put more tools at teachers’ fingertips, unlocking a wide range of brilliant learning activities. After all, teachers will always be the driving creative force within the classroom – it’s about empowering them to do what they do best,” Mr Port said.

“Managing content for interactive displays should be seen as an opportunity. Where teachers have traditionally created individual lesson materials and worked from textbooks, there’s now much more scope for resource sharing and collaboration within schools.

“Some lessons may draw directly from online apps and resources like Google Maps. Without needing to create significant content beforehand, teachers can take students on an interactive journey through environments they’ve been exploring during lessons.

“Students could also be encouraged to share video or photography projects – or take a multimedia approach. Students enjoy seeing their work come to life, and it can act as a springboard for peer review and discussion activities.

“Crucially, modern interactive devices represent an investment which makes a difference across the curriculum – from STEM subjects to arts and humanities. Schools can make conscious, futureproof investments that support their staff for years to come.”

Martin Moelle, Managing Director of BenQ Australia, outlines how classroom technology is re-engaging students. “As collaborative technology like interactive displays continue to develop, they increasingly mirror the functionality of some devices, like mobile phones. With built in Google enabled Android operating systems and familiar apps and experiences, students are being drawn back to lesson content. Kids especially want to use these devices to participate and collaborate, resulting in curriculum being delivered in an engaging and gamified way.”

“For teachers, access to a powerful collaborative whiteboard allows for preparation, control, and delivery of lesson content. Having the ability to change and manipulate lessons on the fly can breathe new life into restricted and tethered lesson plans.

“Having network and cloud drives connected to the display can save time and hassle, when sharing and accessing files, often with several options within tapping distance. To go a step further, teachers can even log in with an NFC card, giving them access to their own personal workspace and files without having to type their passwords in front of students.”

As well as improved learning outcomes, Mr Moelle pointed to the health and safety benefits of classroom technology. “Having a device that offers not only amazing functionality, but also safety features like germ resistance, eye care and physical design elements can assist educators in delivering their “healthy classroom” promise to students and their parents. With classroom air quality still inadequate in many learning spacing, being able to measure and track metrics like CO2 concentration is invaluable when keeping engagement and attention at the highest level.”