The ACT Legislative Assembly recently passed a motion to ban banking programs, like Commonwealth Bank’s Dollarmites, from schools later this year.

The move comes a few months after Victoria announced it would also ban such programs in state schools.

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s (ASIC) two-year review of school banking programs was released in December 2019. It found, among other matters:

young children are vulnerable consumers and are exposed to sophisticated advertising and marketing tactics by school banking program providers.

But our research suggests many young children are aware of marketing tactics, and not as vulnerable as we think.

The banking programs

Much of the criticism of school banking programs has been directed at the Commonwealth Bank’s Dollarmites (running in Australian schools since 1931). But the ASIC report found at least ten such programs were active across schools nationally.

While around 63% of Australian primary schools had joined a school banking program, most primary school students (92%) did not participate or have accounts.

I’ve been with @CommBank for nearly 30 years – I opened a Dollarmites account in primary school and haven’t thought much about which bank I’m with since. I’m beginning the transition away from the Commonwealth Bank today. pic.twitter.com/pHEqt3yNDd

— Emily van der Nagel (@emvdn) January 20, 2020

A survey of 1,349 Australian residents found most (84%) parents with children participating in school banking programs were satisfied with the program and 63% supported financial institutions offering bank accounts to students through school programs.

But the survey also identified 51% of parents had concerns about financial institutions marketing to young primary school students.

The inference children are vulnerable consumers appears to drive the narrative toward removing such programs from schools.

What’s a vulnerable consumer?

Vulnerability stems from consumers who enter service exchanges with some type of disadvantage. These might be personal or social characteristics, which may lead to discriminatory — or even predatory — actions by providers.

Many consumers find themselves vulnerable because they lack expertise regarding the services they are purchasing (such as financial services or insurance).

Children have long been viewed as particularly vulnerable in society, especially when it came to the sophisticated marketing of products like junk food, cigarettes or alcohol. There have been strong arguments to ban marketing communications targeting children in many countries (such as in Europe, the United States and Australia).

Yet, a 2017 review of studies and tests on the vulnerability of young children as consumers concluded:

Although the bases and measures of children’s vulnerability have existed for over 40 years, little of this research has been able to link children’s vulnerability to their consumption. A review of these tests reveals causes for inconsistencies and their implications for further research and public policy remedies for children’s vulnerability.

We put it to the test

Children under eight years old are viewed as especially vulnerable to marketing communications because they do not have sufficient knowledge about “persuasive advertising messages”.

We showed a video of a toy advertisement to 233 children, aged four to seven. We were conscious the young children may not have the verbal ability to articulate responses to questions. So we used images of children’s movies, television programs and advertisements so the children could identify what they believed was the nature of the toy advertisement. Children could select whether they thought it was a movie, a TV show or an advertisement.

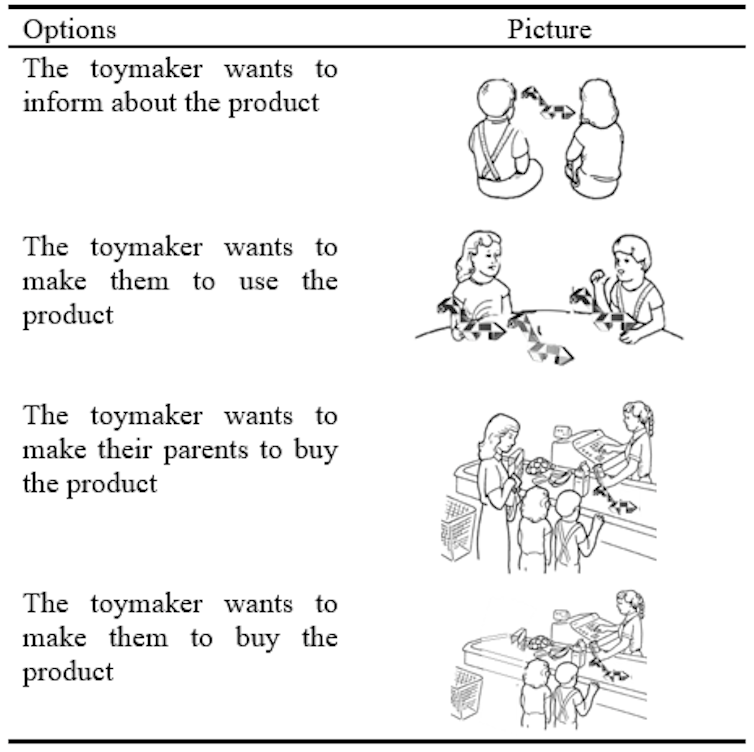

We then used other images for children to identify whether they believed the source of the advertisement was a toy manufacturer, a teacher or a parent.

Children could also indicate the intentions of the adverts, such as “because they want you to know about the toy” or “because they want you to buy the toy”.

More than 75% of children knew four to six aspects of the persuasive advert.

For example, 76% knew the “toymaker made the advertisement” and 82% knew the “toymaker wanted to encourage children to use the product”. Although only 37% knew the “toymaker wanted them to buy the product”, children in that age group have less opportunities to use or see cash.

While many people may think children know nothing about advertising, our study showed most children could identify the nature and intentions of persuasive advertising.

We extended our study to see if children could make responsible financial decisions. We found children who earned pocket money were more likely to save money and reject the offer to buy an advertised toy.

Over-regulation could have negative effects

While the ASIC report is valid and balanced, the response to remove banking programs from schools may unintentionally negate the social and economic benefits of such programs.

Even if the Dollarmites program doesn’t educate children on consumer behaviour directly, marketing plays an important role in socialising consumers. It can help them understand their consumer rights, how to use unit pricing or how to save money.

Over-regulation may generate reactance. Consumer reactance occurs when a consumer feels lack of control over their choice and when behavioural freedom is threatened.

For example, children may only learn about products from their parents or friends based on their preference or knowledge. This means they may never get the opportunity to choose or practise their own coping strategies for marketing persuasion.

While most parents might be cautious about school banking programs, our results indicate children can demonstrate responsible consumption behaviours, save their pocket money and can identify persuasive advertising messages.![]()