In Indigenous education, we constantly hear bad news stories of children falling through gaps and schools unable to assist students who need the most help.

As an Indigenous woman and researcher this affects me greatly, and to the general public, creates a malaise and apathy that disables any tangible solutions.

I’m currently working on a research project about how these negative stories impact on Indigenous education, and I am tired of seeing what doesn’t work.

But there are positive stories of success in Indigenous education – stories that show there is great hope in the way Indigenous communities provide solutions for their children.

I’ve seen many positive and inspiring programs that show that things can be different. Isn’t it time that we focused on a successful story on Indigenous education, and ponder what lessons could be learnt from this?

The Murri School – a success story

The Aboriginal and Islander Community School (The Murri School) is a great example of a school working constructively for all of its children.

For over 30 years, this independent school has been quietly achieving results. Growing from a small derelict building in inner city Brisbane, the school now resides in Brisbane’s south and is large enough to cater for their students.

The Murri School is focusing on the practicalities such as busses to get children to school, and using a holistic approach that gives families empowerment in school decision making.

This school is one of the few Indigenous owned and controlled schools in Australia.

It has around 208 students ranging from Prep to Year 12 and uses creative ways to encourage the success of its students. These include close connection to health services through which it employs a family support worker, speech pathologist and a number of psychologists and counsellors. The school was established on the assertion of real sovereignty and self determination.

School Board President Dr Valerie Cooms says that part of their success is due to strong female involvement:

We work closely with mostly mums and grandmothers and some fathers too, from the enrolment process right through to assessing individual student needs (health and wellbeing) as well as assessing their literacy and numeracy capabilities.

As a PhD candidate researching Aboriginal women and leadership, the involvement of these women comes as no surprise as it appears the work that many do in education is often of a volunteer nature, yet tireless in its approach to building a strong autonomous school environment.

This goes beyond the nurturing idea of women’s leadership towards strong and determined capacity building, governance and advocacy.

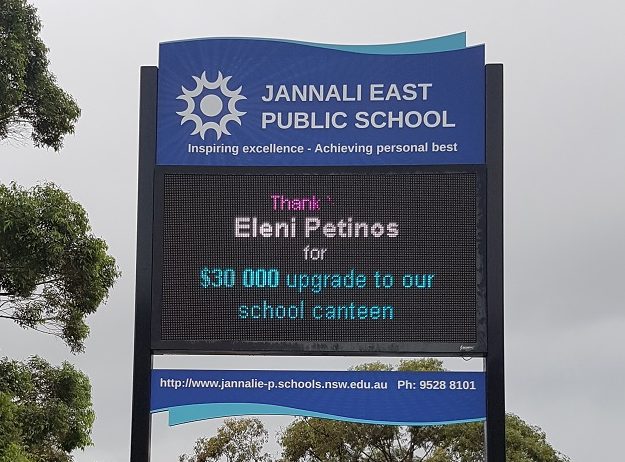

Autonomous schools look beyond government targets

Autonomous schools have to work intensely with both government departments and the community in order to provide an effective school environment.

The process of establishing such a school is more than building classrooms, playing fields, tuckshops, and administration offices. It is also moves beyond achieving government-based targets. As Cooms explains:

It’s more than just assessing academic skills, we want our students to learn how to communicate and navigate the complex world around them. Cultural pride and identity as Indigenous people is key to learning academic and socio-cultural skills.

Moreover, parents and other care providers feel comfortable communicating their concerns or needs in our school because we are community based and owned organisation, not a program designed and implemented from elsewhere. Its home grown.

The school provides a range of activities for a dispersed population and has multiple roles, including service provider and the “voice” of the community on many issues. The school also employs many Indigenous people.

[wpdevart_youtube]AyLyiIF4LEs[/wpdevart_youtube]

Some of the positive programs run through the school have included healing camps, run with both students and family members, and the inclusion of a Family Support Service. This service supports families in their day to day struggles in crisis intervention, prevention, advocacy and support.

These elements connect strongly with the school’s desire to include parents in the school environment, thereby involving them in their children’s education.

For Indigenous children, the education curriculum can be full of white representations that often don’t resonate.

Together with the impact of stereotyping on these children, this suggests that having a school where there is a dense population of black faces helps build an environment where students can feel comfortable.

The most exciting thing about many of these programs is that they go well beyond trying to close gaps. These programs, in their own unique ways, achieve far beyond the targets that the government has set.

For instance, the Murri School doesn’t just aim to improve literacy or attendance, it also recognises the value of parents and community being involved in educational decision-making for their child’s future. It also sets the bar high by working at building pathways for Indigenous employment, such as traineeships for Year 12 students.

The example of this school highlights not only the success in Indigenous owned and run institutions, but poses the question of why we don’t have more of these stories in the education system.

There is more that needs to be done in Indigenous education, and parental and community involvement shows just one way that the disadvantage can be addressed.

In light of all the bad news, how refreshing is it to hear and witness the hope and enthusiasm that exists in spite of this negativity? Why are there not more Indigenous schools, and is community ownership the way to change the disadvantage we hear in Indigenous education? It is time we shifted focus and celebrated more of these success stories.

![]() This article was written by Tess RyanFirst published on The Conversation.

This article was written by Tess RyanFirst published on The Conversation.