Making critical literacy decisions: What comes first?

Katharyn Cullen and Denyse Ritchie from THRASS Institute explain why early readers should be taught letter names, not just sounds.

The development of literacy is closely tied to the practice of handwriting, which integrates with the learning of letter names and sounds. The path towards literacy begins with preliteracy, which involves familiarity with the alphabet, letter names and letter patterns to represent written sounds (phonics). However, there is much controversy surrounding the order in which letter names and letter sounds should be introduced.

Read the latest print edition of School News HERE

Research indicates a strong correlation between children’s ability to identify letter names and their future success in reading skills, establishing it as a crucial early predictor of future reading achievement (Trieman & Wolter, 2020). Furthermore, the more letter names a child knows, the better their chances of success in decoding with an understanding of letter names significantly boosting their grasp of letter sounds (Share, 2004). This is due to the role of letter names acting as a “hook” or “anchor,” connecting the sounds children hear to the spellings they write down, thus providing essential labels for letters.

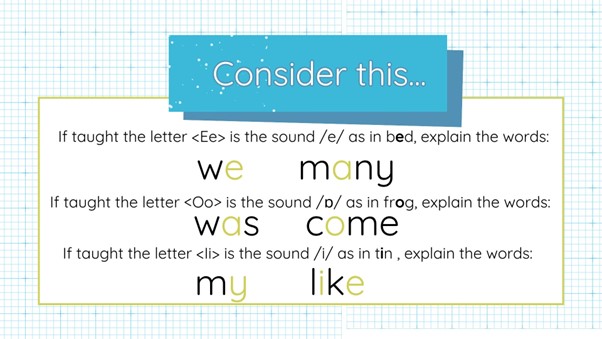

Although many argue for the teaching of ‘letter-sounds’ first, this ‘letter-sound’ label can be detrimental for young learners. For sustainability in phonics teaching, letters must be labelled by name to enable the ongoing teaching of the whole phonics code of English.

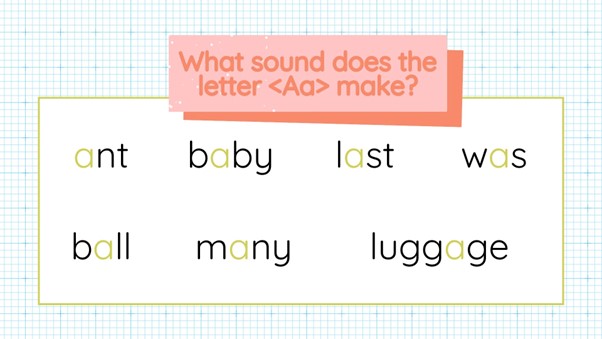

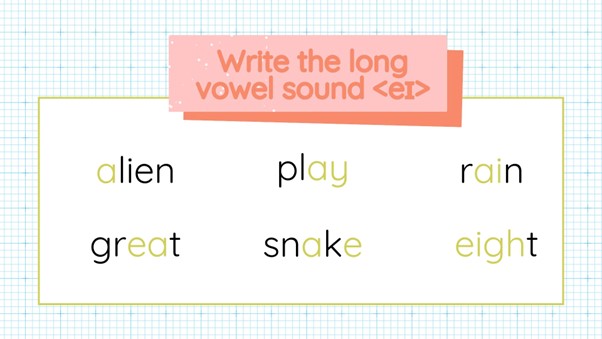

The labelling of ‘letter sounds’ does not allow the understanding that multiple letters can represent the same sound in English or that the same sound can be represented in multiple ways.

Using letter names is therefore a reliable way to refer to and teach spelling patterns (graphemes) and provide clarity in understanding how to write phonics patterns (graphemes) in words. In English, letter names provide a stable and consistent property that supports students’ understanding, given letters do not have a single sound value.

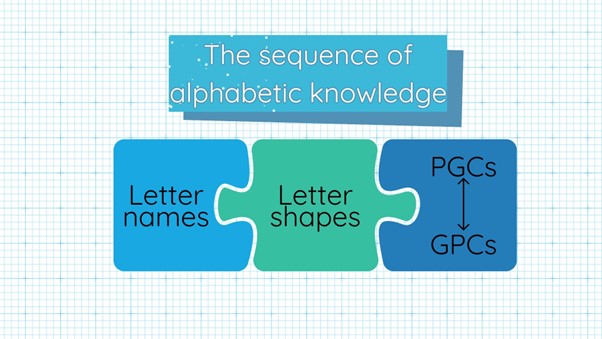

As such, we suggest teaching alphabetic knowledge in a sequence that begins with letter names, then letter shapes, and finally phoneme-grapheme correspondences and grapheme-phoneme correspondences.

Undeniably, there exists a complex connection between letter name knowledge and phonics knowledge, where recognising letters – the symbols of our written language or code- is essential. But, if the focus on early literacy education is purely on teaching ‘letter-sound’ phonics, a process where each letter of the alphabet is given one corresponding sound, it risks undermining the teaching of handwriting as well as comprehending the written code. Explicit teaching of handwriting instruction, with a focus on learning both letter names and phonics, can be experienced concurrently allowing for the benefits of both approaches.

Practical Implementation: Why educators should refer to letter names when teaching handwriting and reading

Physically writing letters is crucial for building a solid cognitive understanding of how the phonics code works. By learning and practising handwriting, students gain more confidence, improved dexterity, better recall and enhanced memory, all of which are vital for phonics instruction. When students learn to write letters correctly and can recognise them by name, they not only improve their handwriting skills but also advance their ability to identify and read letters fluently. The physical act of forming letters helps children internalise the shapes, curves and details of each letter, which in turn enhances their ability to recognise and differentiate letters when reading (Jones et al., 2013).

Therefore, it is important for young learners to have daily and deliberate opportunities to practise forming letters while connecting them to their corresponding phonemes, enhancing students’ retention of grapheme-phoneme correspondences. This integration nurtures cognitive abilities such as letter recognition, reading, spelling and word knowledge.

Katharyn Cullen is an experienced Head of Junior School, innovator and curriculum specialist who is currently completing her PhD in multiple-linguistic word-study instruction. Katharyn regularly shares her work at both state and national conferences and actively demonstrates and supports teachers in classrooms across Australia.

Denyse Ritchie is an Honorary Chair of Literacy and Fellow at Murdoch University, WA and has over 40 years of teaching experience. Over the past 25 years, her focus has been on the teaching of literacy and the role of phonics in both foundational literacy and across the grades. Denyse is the co-author and developer of The THRASS Specific Pedagogical Practice and, Principal of The THRASS Institute, Australasia and Canada.

References:

Jones, C. D., Clark, S. K., & Reutzel, D. R. (2012). Enhancing alphabet knowledge instruction: Research implications and practical strategies for early childhood educators. Early Childhood Education Journal, 40(2), 101-107.

Share, D. (2004). Knowing letter names and learning letter sounds: A causal connection. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 88(3), 213–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2004.03.005

Treiman, R., & Wolter, S. (2020). Use of letter names benefits young children’s spelling. Psychological Science, 31(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619888837