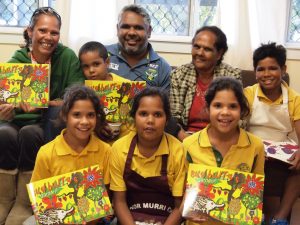

Budburra Books: Strong Indigenous culture, great results

Not-for-profit organisation, Budburra books celebrates the strengths and creativity of a ‘deadly’ Indigenous school and community.

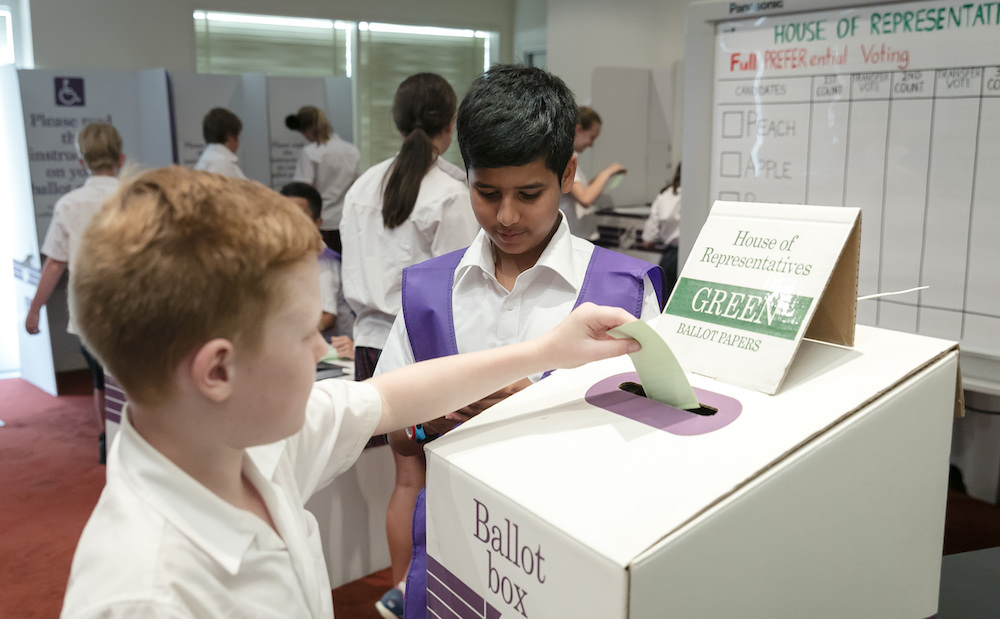

The students at Cherbourg State School, an Indigenous school in south east Queensland, have proved that they are talented authors, artists and filmmakers. They have produced 12 beautifully illustrated books and five films.

Budburra Books engages students and community members in the production of books, art and films, by drawing on the cultural strengths, historical ties and artistic skills in the community. The project aspires to encourage a love of learning and literacy and continue cultivating pride in local Indigenous culture.

Producing Budburra Books embeds cultural awareness, local knowledge, interests and creativity for students and provides pathways to explore careers as authors, artists, designers, storytellers, scriptwriters and filmmakers.

The published books are designed to be a supportive teaching tool that allows several skills and strategies to be employed across a range of learning areas, including Indigenous perspectives.

The books provide language and literary value and are visually engaging. www.budburrabooks.com.au