EXCLUSIVE: Wednesday Weeks’ authors spot the challenge for educators

In this two-part Science Week series, School News speaks to kidlit authors Cristy Burne and Denis Knight about the message teachers should be telling kids about science.

“The entire scientific method is based on trying and failing and then learning from mistakes,” Knight and Burne explain, but “science can’t solve our problems.”

“Perhaps everything we know about our world has been learned in this way. Yet so many students are terrified of failure.”

Popular children’s authors, both Burne and Knight are experts in the cross-over between creativity and science: they co-author the Wednesday Weeks series of books about a reluctant magician who’d rather be a scientist.

“In writing the Wednesday Weeks series, we wanted to show a character who isn’t perfect, who doesn’t get it right every time, but who learns from mistakes and tweaks ideas and digs in when it counts. Because science requires grit. So does saving the world. And so does getting out of bed and giving your best every day.”

“Only people can solve our problems,” they agree: “And that makes science and technology vital tools in our toolbox. To combat issues such as climate change, global inequality, and environmental conservation, we need creative thinkers who can apply what they know in innovative ways.”

“We need dreamers who can invent new ways to make our world a better place for everyone. We need makers and doers and creators who are brave enough to make a difference. And we need teachers to inspire them.”

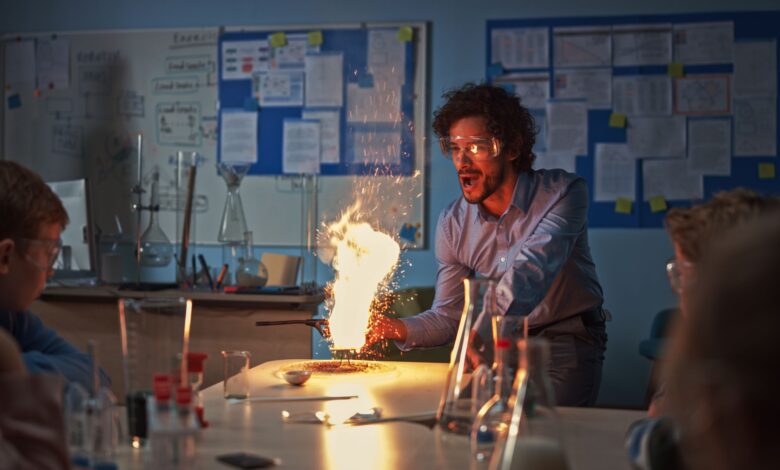

Burne has been a science educator for twenty years and a writer for more than fifteen, with a deep passion for blending STEM, literacy and creativity, and believes: “Kids need to know that science is curiosity: the drive to discover new things. And science is creativity: the freedom to try and fail and learn from mistakes. And most of all, science is fun: it’s everything from our expanding universe and pink slugs to flying cars and giant squid and more. Science is limited only by our imaginations.”

The challenge for educators, Burnes adds, is to channel these powers for positivity:

“Screen time can be mindless and numbing. But it can be also creative and inspiring. Somehow, we need to hook kids on the satisfaction and excitement of making something they’re proud of.”

And teachers should keep in mind that this new crop of students “know more about the world – and its opportunities – than any other generation”.

Importantly, “thanks to Covid-19, our kids have witnessed what we can achieve when we work together. Thanks to vaccines, they’ve experienced scientists as heroes.”

Wednesday Weeks book series covers, Hachette Australia

Encourage students not to self-exclude from science opportunities

This combination of witnessing striking real-time scientific developments, the immediacy of the internet, and the ability to access previously inaccessible knowledge and information, gives students an edge but schools have an important role in helping students consolidate their experiences to understand how new science pathways and learning areas can apply to them.

Burne was at high school when she realised that “studying science would open a million new doors” and isn’t this the message we should be sharing with all students? Students who don’t view themselves as ‘science kids’, the bookish students, the creative students, the sporty students, they can all benefit from science-led opportunities.

Likewise, Knight got into science in a roundabout way. Like many kids of the 1980s he grew up wanting an Atari 2600 games console, but his parents thought a TRS-80 computer was more educational. He says he taught himself BASIC programming and wrote a ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ game that failed to impress his Atari-owning friends, but triggered a love of computer science instead.

For young learners, the most important Science Week takeaway should be summarised as Burne and Knight suggest: “Be brave enough to walk your own path and others will follow. Your voice matters. Your creativity matters.”

Science Week (August 13-21) is an annual celebration of science and technology, and the contributions of scientists to the world of knowledge.

Teaching resources for Wednesday Weeks book series: https://cristyburne.com/resources/free-stuff/wednesday-weeks-resources/