Technology and learning in the classroom: six tips to get the balance right

Australia was one of the first countries in the world to have more computers than students in schools. But as the numbers of computers and other technological devices increased, student performance did not. The days of cramming computers into classrooms and expecting improvements in learning are numbered.

Some argue there’s little evidence to justify investment in technology in the classroom. In fact, some studies even suggest potential harms. Some have suggested links between screen time and increased ADHD, screen addiction, aggression, depression, and anxiety, dizziness, headaches and blurred vision.

There is also a risk that schools’ focus on acquiring the “next best thing” may come at the expense of students’ interpersonal, cognitive, critical thinking and communication skill development. Teachers should use technology in a balanced way that enhances learning and skill development. Here are six evidence-based tips on how to do just that.

1. Use two (or more) ways of communicating

There are endless opportunities for students’ writing to appear in ways that combine two or more modes (such as visual, audio or spatial). Making e-books, videos, animations, blogs, web pages, and digital games are the new ways of demonstrating literacy that involve clever combinations of these modes.

Words are rarely used on their own on digital platforms now. Instead, they’re illustrated with images, screen layouts, pop-ups, hyperlinks, and sounds to create meaning in different ways to, say, an essay.

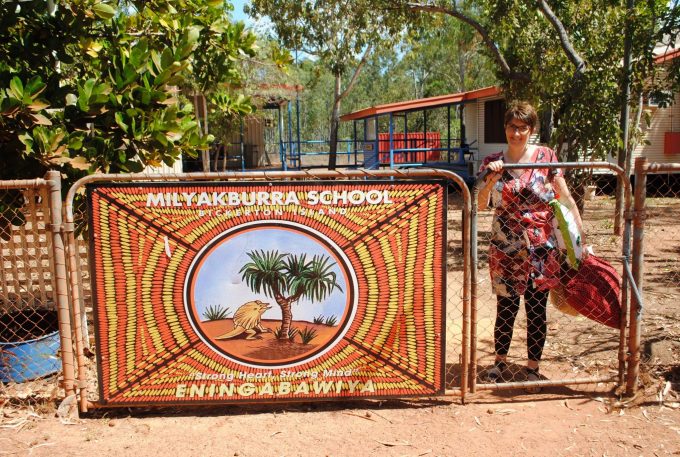

Multimodal literacies are actually a requirement for students in the Australian curriculum. More than 200 learning outcomes address this type of literacy, right from foundation (prep) to year 12. Supporting children to create multimodal designs, even something as simple as creating a digital drawing or diagram, is a fantastic way to ensure educational benefit when using technology.

Nearly half (44%) of current jobs are at high risk of being digitally disrupted in the next 20 years. The fastest-growing jobs now require multimodal design and digital communication skills, for example engineering or architecture.

2. Channel creativity

Look for opportunities for students to produce rather than consume, and to be interactive and creative. Don’t just play educational games – make them. Students shouldn’t be sitting passively watching a screen, or sitting through lecture-style content while watching the teacher flip through slides.

Avoid educational software that simply requires students to engage in closed answer, “fill-in-the-blank” responses. While sometimes useful for memorising information, such as spelling words, using platforms that encourage creativity and support children to think for themselves is better for learning.

Try to choose technologies that support interactivity, critical thinking, and problem solving. Examples include educational games that allow exploration (e.g. The King’s Request), or websites that encourage the learner to solve problems (e.g. Scratch), write basic code (e.g. Hour of Code), express their creativity (e.g. Stencyl) or build something (e.g. Roblox for education).

3. Choose collaboration

Give students opportunities to work together in learning and engaging with digital media. Collaborative digital activities can be used to engage students in higher order thinking skills and explore content in depth with the support of classmates.

This includes devices and software that allow multi-user learning and encourage students to interact with each other. This includes interactive discussion boards, or applications such as “minecraft for education” where students can experience a digital learning environment together.

Incorporate “distributed expertise”, where classmates help each other out in areas of digital strength, rather than seeing the teacher as the only expert. This has been shown to have great benefits in developing students’ soft-skills (such as creative thinking, communication and teamwork).

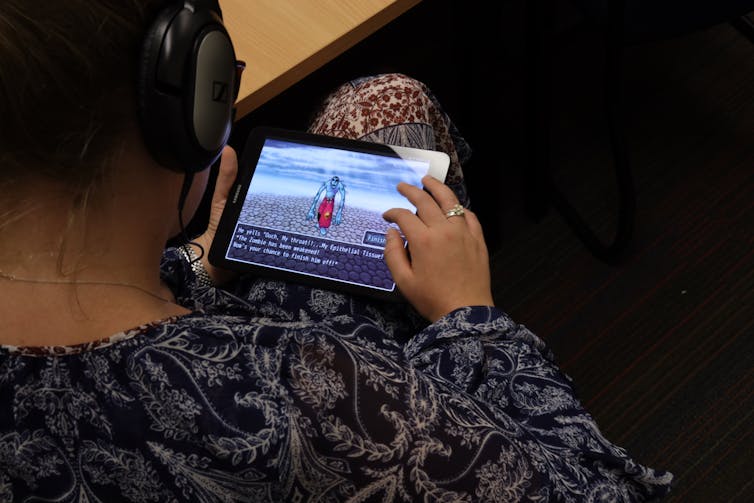

4. Movement is key

Many digital technologies involve more sensory involvement than in the past. Using virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) or mixed reality (also called hybrid reality – where digital and physical objects co-exist), can encourage children to be active physically while using their brains.

Research shows moving can help keep the brain active. Cognition is deeply connected to the child’s bodily interactions with the world, so technology use and learning doesn’t need to be motionless!

This can include placing QR-codes (markers) around the room for them to scan, or the student using augmented reality apps where their smartphone or tablet is used to render 3D objects, text or animations on the screen when the camera is pointed towards a marker. An example of software capable of performing this includes Augment, which also offers specific instructions and accounts for educators.

5. Media-free moments

While research supports the many benefits of using modern technologies for learning, there are guidelines for managing time with technology. Teachers and parents should establish media-free zones, and set content and time limits appropriate to age and the curriculum.

Removing smartphones, turning off computers and keeping an area completely technology-free at regular times during the day is important to establish healthy habits with technology.

6. Support cyber citizenship

Teach students digital etiquette, how to present and protect themselves online, and how to be critically literate. Model good digital citizenship and behaviour, and always be ready to learn. Adults can’t assume children know how to interact safely and responsibly online.

Research shows critical skills are often lacking among primary students. Teachers and parents have an important responsibility to show students how to critically evaluate how reliable online sources and other media are.

Christian Moro, Assistant Professor of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Bond University and Kathy Mills, Professor of Literacies and Digital Cultures, Australian Catholic University.This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.