Australia is home to one of the oldest continuing cultures on Earth, with history and traditions of First Nations people spanning an estimated 65,000 years. This is something all Australians should be proud of, and should work to preserve, celebrate, and continue.

At the time of colonisation, there were more than 250 individual and distinct Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages spoken in Australia. Of the 145 left today, 110 are critically endangered. Indigenous languages in Australia comprise only two percent of languages spoken in the world, yet represent nine percent of the world’s critically endangered languages.

Read the Term 3 edition of School News HERE

In October 2022, the Federal Government committed to a $14.1 million plan over four years to 2025-2026 to teach First Nations languages in primary schools across Australia. Funding would support 60 new First Nations Cultural Educators to share their language and culture in primary schools throughout the nation. The initiative aims to help keep First Nations languages alive, by increasing the uptake of these languages by young people. State and Territory governments also have programs which facilitate the teaching of First Languages in schools within their jurisdiction.

Minister for Indigenous Australians, Linda Burney, said the Government is committed to safeguarding and strengthening First Nations languages.

“Indigenous languages are so important to the identity and connection with culture for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

“Promoting the use of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages in health and early childhood settings demonstrates our collective support and drive to achieve positive health and wellbeing outcomes in First Nations communities,” Minister Burney said.

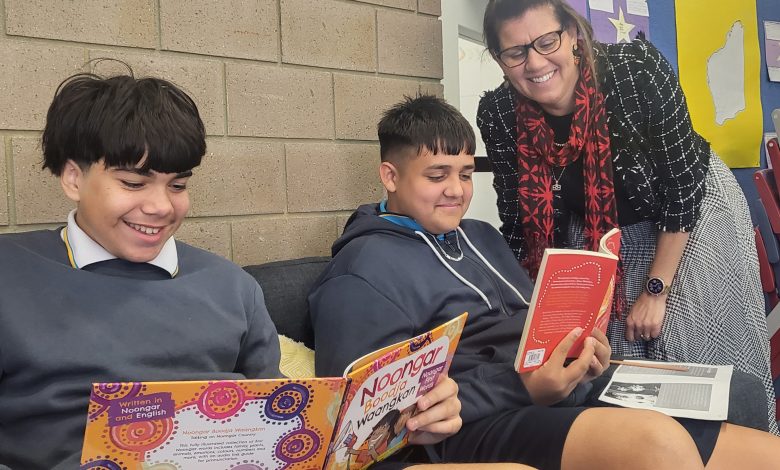

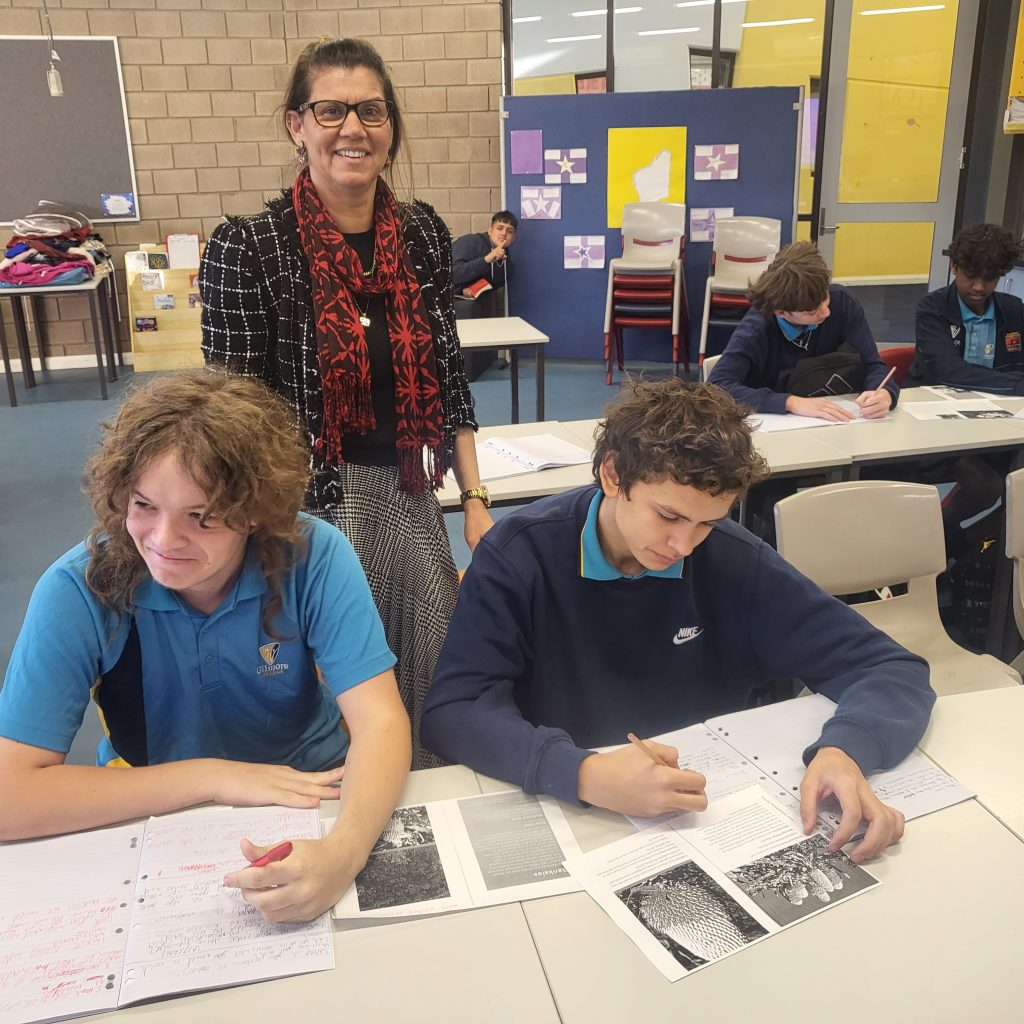

Isobel Bevis is a qualified Aboriginal Languages Noongar Language teacher. Based at Gilmore College in Western Australia, she works with Aboriginal students, connecting them to history, culture, and language.

“The kids love it,” Mrs Bevis said. “They pick up the language through stories, games and conversations about language. Linking language with history and culture helps them to better grasp the language, and to recognise words and how they are used.”

Mrs Bevis said she grew up with language, listening to her nan and uncle speak and picking up words, though she was not a fluent speaker. It was later in life, when she was deciding on a career path, that she took to studying the language more rigorously.

While working as an Aboriginal Education Officer, she received an email seeking applicants for an Aboriginal Languages training course. Candidates did not need to be fluent speakers, but did need to have a basic understanding of the language. Completing her qualification in blocks, Mrs Bevis studied for one week during each school term, and then one week in the school holidays.

Once qualified, Mrs Bevis divided her time between working as an Aboriginal Education Officer in a high school, and teaching Noongar language in a primary school.

“I was new to teaching, and then new to languages when I first started teaching Noongar,” Mrs Bevis said. “I didn’t think it would work, but it did. I learnt alongside the children, and we taught each other.”

Research conducted by the Australian Council for Educational Research reported that 16,000 Indigenous students and 13,000 non-Indigenous students in Australia are involved in an Indigenous language program. More than 80 different languages are taught, in 260 Australian schools. The number of students taught, schools involved, and languages represented varies from state to state. As of 2022, Western Australia and South Australia lead the sector, with 68 and 63 schools teaching language respectively. First Languages are delivered to 49 schools in the Northern Territory, and 46 schools in Queensland.

Why teaching First Languages is important

Reconciliation Australia sees the maintenance, revitalisation, and revival of First Languages as important acts of reconciliation. Research emphasises that intercultural awareness and understanding is increased for all involved in language revitalisation initiatives. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who speak First Languages are also more likely to attend school, gain a post-school qualification, be employed, and have markedly better physical and mental health.

The preservation of First Nations languages, then, is about more than the languages themselves; the impact for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and for the country more broadly are far reaching. Reconnecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with their languages can help close the gap between Indigenous educational, socio-cultural, economic and health outcomes or opportunities compared with those of the wider Australian community.

Language is an important tool for conveying knowledge, understanding, history and culture. All students benefit from learning First Languages, as they offer the opportunity to learn about First Nations history, culture, and contributions. It also helps reframe Australian history, accepting the old version of European settlement is inaccurate and disrespectful of First Nations people. Language revitalisation can support the development of bi- or multi-culturally aware and appreciative citizens that can drive a future of shared pride among all Australians.

Collaboration with local communities is facilitated through local languages. And, with the loss of language also comes the loss of Indigenous ecological knowledge, including Aboriginal seasonal knowledge and traditional uses of flora and fauna.

Students want to learn First Languages

A 2022 poll of primary school students revealed they would rather learn a local First Nations language that the commonly-taught Japanese, Mandarin, French, Italian, German and Indonesian. Commissioned by the Know Your Country Campaign, the survey also found that nearly a third (28 percent) of parents wanted their children to learn a First Nations language.

Campaign advisor Professor Tom Calma, AO, from the Australian Literacy and Numeracy Foundation, said: “The findings show a genuine hunger from both parents and children themselves to be authentically taught more about the country’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and languages.

“Wouldn’t it be great if the local First Nations language for ‘hello’ rolled off our children’s tongues as easily as Bonjour or Ciao?” he said.

Speaking with Know Your Country following the survey’s release, Know Your Country Policy Lead and Wiradjuri man Dr Scott Winch said “There’s an incredible power and investment in knowing the history and unique language of the land you are standing on. When children learn directly from a local First Nations educator, our research shows they are more likely to enjoy the class, and develop a thirst to learn even more.”

Mrs Bevis believes there has been a growing momentum for the revival of First Languages. She attributes this in part to the increasingly common trend towards dual place names. “Community have more input with local councils now, and are asking for traditional place names to be recognised. Schools think they should encourage this,” she said. “Using traditional place names then allows the community to identify what country they are on, and what language should be spoken in that area.”

The challenge

While the greater interest, recognition and uptake of First Languages is encouraging, Mrs Bevis said a shortage of Aboriginal language teachers is one of the biggest barriers. “Noongar Boodja (Country), where I live and work, is the largest language area in Australia. Finding people to learn and then teach the language is difficult.

“You can’t have reconciliation without language,” she said, and cautions that explicit teaching is not always the best approach. “The teaching of language in the curriculum is very structured, it is through a Western lens. This doesn’t always work, though. Do we have to use the curriculum, or can we get the local community and Elders involved?”

Much of Mrs Bevis’s teaching is student led and enquiry based – students notice language conventions in their learning of history and culture, which they can then discuss and understand. Mrs Bevis also adapts her teaching strategies to suit her learners.

“The kids I teach may not use Noongar every day, but they will understand it when they see it or hear it.”

This could prove a useful model to engage all students with First Languages. Shifting the goal from fluent speaking to an appreciation, understanding and recognition of First Languages could make them more accessible to students, and the community more broadly.

For Mrs Bevis, learning and then teaching Noongar is about more than the language; it is a way of honouring her mum and siblings, and her nan. “My Nan, through the Native Citizenship Act, gave away her rights to be Aboriginal after colonisation so she could attend school and then raise her children. She stopped speaking her language, and much of her culture. Teaching language, history and culture to students is my way of repaying Elders, those who have gone before me, and helping the next generation reconnect with their past and who they are as Aboriginal children.”

This is a mark of respect we can all extend to First Nations people, encouraging the learning of First Nations language, culture and history for everyone.