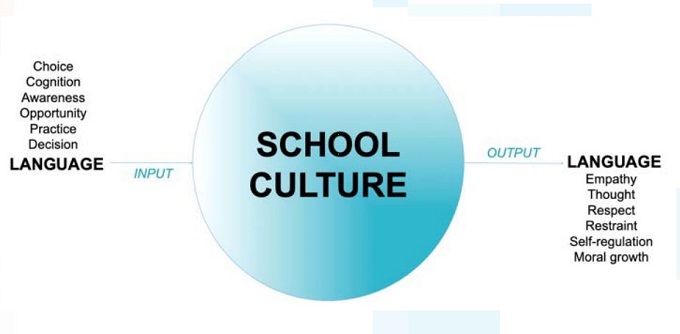

Language in, language out: a basic model for school culture

I was recently working with some School Leaders and I devised a basic model on the run with them about School Culture.

When I came home from this particularly engaging session I looked upon my new hastily conjured model, perhaps pondering just how clever I was to have spontaneously designed such a neat artifact, I realised that I may have gotten one small detail wrong – my audience.

Here’s the model. I’d love to know what you think:

To be up front, what I think I got wrong in terms of audience is that this model is probably far more important for Classroom Practitioners than it is for School Leaders.

Allow me to explain why. Language as an Input All of the literature around classroom climate/culture points to the importance of the language chosen by those with authority. Think about a family for a moment.

The language choices made by the parents/caregivers is directly teaching the learners of the culture, in this case their children, what matters, what’s important, what the rules and what the norms are within that little family culture.

As it is with Teachers. Your language choices are Teaching your students what’s ok and what isn’t in your classroom.

On the positive side, if you were to choose to speak effectively, meaning that you use statements that incorporate feelings words through statements like “I’m really frustrated with the choice you just made. I need you to make a better one now.” as opposed to “Hey, cut that out!” then you teach your students to be more empathic.

On the negative, if you fly into threats or raise your voice at the first sign of a bad day, then you teach your students that this is an acceptable response to frustration.

In my model, the words on the input side are a reminder to you that this is first a choice or decision to change language. But more than the choice, you’ll need to practice these simple language shifts in order to move through strong levels of self-awareness towards a new linguistic default.

Language as an Output In time, the persistent deployment of positive and affective language in your practice is more likely to generate students who are:

• Empathic – because they’ve learned to care through exposure to the language of care, almost via some version of verbal Chinese water torture.

• Thoughtful – they begin to actually think before they act, rather then merely contemplate potential punitive consequences and how to avoid them.

• Restrained – they pause for a moment to allow space for wise decision making before making impulsive behaviour choices.

• Creative – they create for themselves better behavioural responses, even under pressure.

Further, when they do get it wrong, they’re more creative about devising appropriate responses to poor choices – because they will continue to make mistakes.

What we want is for these moments to be seen as opportunities to practice that relational creativity, rather than sources of personal shame.