Yarra Hills Secondary College is a multi-campus college of around 900 students in the outer eastern suburbs of Melbourne, with campuses in Mooroolbark and Mt Evelyn.

Since taking on the role of college principal in 2013, Darren Trippett and his leadership team have prioritised the development and implementation of restorative practices across the campuses; to improve student-teacher and student-student relationships, as well as provide a more stable and orderly environment for student learning.

Why the change?

In reviewing past practices across all campuses of the college, I identified that the default management of student behaviour was very reactive and prescriptive, without much thought of how things could change as a response.

If an adolescent gets a maths question wrong, we don’t just ‘punish’ them and tell them we expect them to get it right next time, we discuss what exactly they did wrong, talk them through why it was wrong, so they understand it and then provide strategies on how to get it right. It is a learning experience. Why do we then default to punishment when that same student gets their behaviour or relationships with others wrong?

In looking into the school’s responses to student management issues, it became clear that staff were struggling to deal with some students, particularly ‘repeat offenders’. Year level coordinators were spending a great deal of their time quashing ‘spot fires’ and there were a large number of subsequent detentions and suspensions as a result. On top of this was the huge workload for these staff members in investigating every incident to find out who was at fault, or to blame, and then the allocation and follow up of consequences. Clearly, what was being done was not working, as the behaviour kept happening

Restorative practices

Around this time, I was attending a principals’ conference and heard Adam Voigt (Real Schools) speak about this very issue. Adam’s philosophy is very much built around establishing and maintaining effective relationships in the school setting, not only student to student, but also student to teacher. A key part of this is encouraging students to actually understand the damage they may have done to their relationships with others, due to incorrect behaviour and to then help them through the process of being better at ‘getting it right’ i.e. restoring the relationship. This resonated strongly with me and shortly afterwards Yarra Hills Secondary College embarked on a partnership with Real Schools to start the process of creating a restorative environment and embedding it in school practices

How?

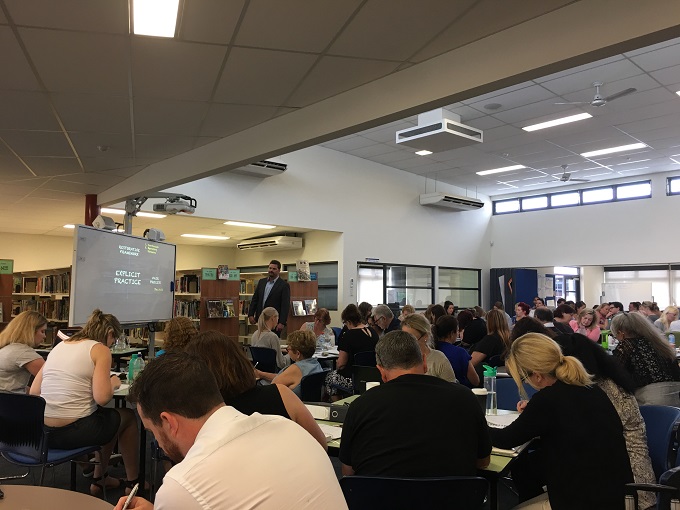

After committing to a partnership with Real Schools, the Yarra Hills leadership team, Adam and I sat down and plotted out a 3-year plan on how to become a ‘restorative school’. The first part of this was all members of the college’s leadership team undertaking intensive restorative practices training with Adam. It was crucial that all leaders were not only familiar with what to do and how to do it, but also that they would be in a position to mentor and guide other staff. These leaders were then given a period of time to test things out in their own ‘real world’ settings to ensure that the model fitted the college, but to also iron out any inconsistencies or issues before other staff were brought on board. Once this team were all familiar and proficient, all other staff were then taken through the same intensive professional development to prepare for whole school implementation.

A crucial part of the implementation was assisting the staff to develop and trial many of the strategies, including the use of ‘affective’ statements (linked to an emotional response) such as “I felt let down when you ……” or “I appreciate the fact that you ….”. These statements not only focus on the link between the action and the effect on the relationship, but they provide the student with immediate feedback on the impact of this. Staff then worked together to develop a ‘bank’ of these statements, which has been added to the college online Moodle curriculum resources, along with many other restorative practice materials.

Another strategy that staff embraced was the use of ‘restorative circles’ in their classes to foster a better environment. In fact, as a part of the partnership with Real Schools and following the earlier PDs, Adam came out to the school and provided in-class support to teachers wishing to learn, try or demonstrate these. In essence, he made himself available to run a class and be observed, assist a teacher with a class, or just observe and provide feedback. These sessions were considered highly valuable by staff, many of who observed others’ sessions and/or tried out their own.

Those staff members in student management positions were also stepped through a number of processes to address higher order issues in a restorative way – with the focus going away from the ‘blame game’ and detective work, to a more consistent, rational approach that allows for a student to understand and learn how to manage themselves and others.

The final piece of the puzzle, before it could be implemented, was to inform the community. Much information was sent out to parents regarding the college’s move to a restorative model, including the reasons for doing so and the expected outcomes. A large part of this was also holding a parent information evening where the college leadership team and Adam ran through restorative practices and how things would be different and why. This is most important because the college needed to have the parents on board when the first instance arose regarding their own child. Again, it is important to not default to blame and punitive measures. Almost without exception, the parents have also embraced the model and do continue to support the college and the procedures

Outcome: where are we now?

While Yarra Hills still considers itself on the journey to full implementation and embedding restorative practices into the culture, the feedback and data has been very pleasing. Anecdotally, staff believe that the classroom environments are clearly calmer, with fewer ‘spot fires’ occurring. Coordinators have found the process particularly effective when dealing with higher order issues, as well as in response to bullying incidents. They also find they have more time available for other things.

Objective measures have shown that there has been a reduction in volatile incidents occurring in class at all year levels, as well as a reduced level of escalation for any incidents that did occur. Student removal from class has dropped significantly, partly on the basis of staff developing better relationships with the students and having a calmer environment, but also due to teaching staff themselves feeling they have better strategies in place to manage concerns in their own class. Despite increasing enrolments, the number of suspensions has dropped across the college over each of the last three years, as well as an associated decrease in repeat offences or offenders. The college’s Attitudes to School Survey data has also shown that students feel safe at school and there is reduced evidence of bullying behaviour.

Where to from here?

As a college, we continue to work on embedding and reinforcing restorative practices, including the inclusion of school student leaders as ‘champions’ within the school. With a growing school enrolment, it has been crucial to also train all new staff in the expected practices, as well as to continue to provide professional development for others trying to improve their own practice. Having now significantly progressed down this path, the most valuable resource for staff seems to be other staff who have trialled, tested and refined these skills.

In summary, I believe that embedding restorative practices across the college has been an incredibly positive development for Yarra Hills Secondary College and one which continues to improve the learning environment for all students.