Today’s teaching graduates spend at least four years at university, living at home with family or in shared accommodation. They travel to university each day by car or bus or ebike, spending just as many hours at their part-time job as they do at university, just to make ends meet.

Read the latest print edition of School News HERE

100 years ago, when car ownership was still the preserve of the ultra-rich, travelling long distances every day was rarely an option. In Western Australia, people who wanted to be teachers had to study and live at the Claremont Training College.

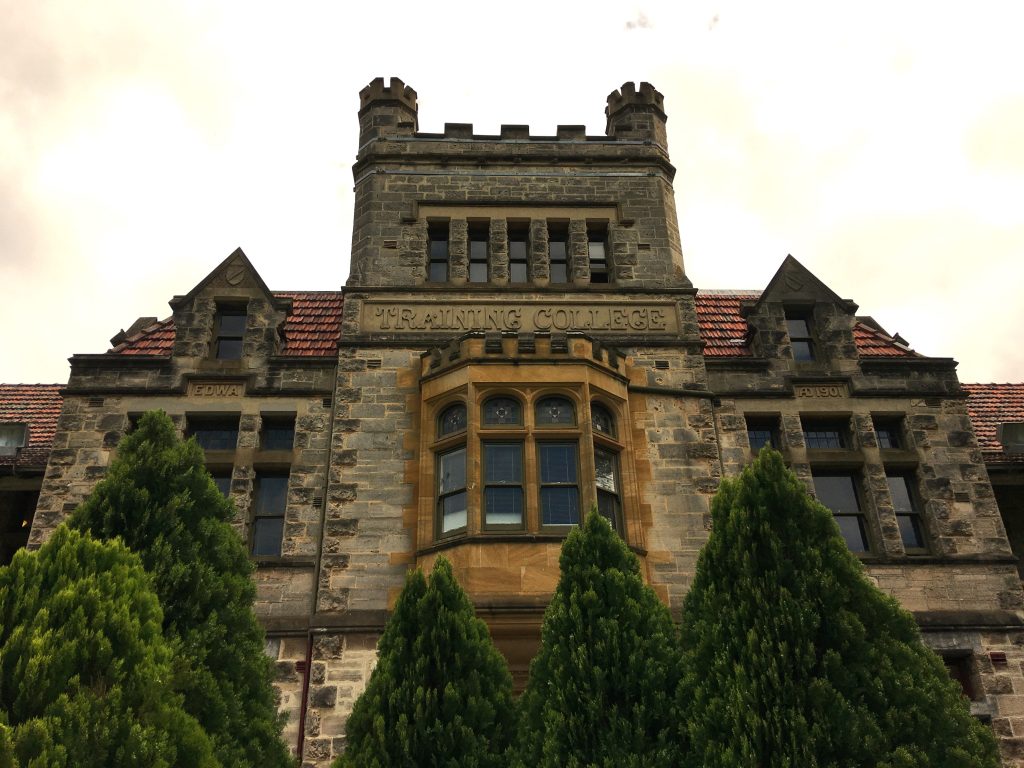

Pre-dating the University of Western Australia by almost a decade, Claremont Training College was built in 1902, the first of its kind in Western Australia. Prior to the College opening, teachers were trained on the job or through correspondence courses from the East, often having little more education than the students they were teaching.

The stately Gothic building, which still exists, had classrooms on the ground floor and dormitories on the top floor; the grand building housing not only dozens of students, but the Headmaster and his family, Matron and various staff.

If you visit today and peruse the College plans that hang on the walls in a lunch room, it is easy to see the vast space the principal occupied compared to students. His residence was the whole eastern wing, two-storeyed and inclusive of multiple bedrooms, a study and a private kitchen and dining room. By comparison, each student had a small cubicle with a bed, a side table and space to hang their clothes. Strictly segregated, male and female students lived in dorms at opposite ends of the building, with the Matron between them.

While the College was one of the very first public buildings in Perth to get electricity, the lights were electric but little else. Heating came from fireplaces in the corner of each room. There was a single telephone in the College, hidden in a small cupboard under the grand staircase. As was the norm of the time, there were no toilets inside the buildings. While there were bathrooms where students could bathe and brush their teeth, the toilets were located outside, at a distance from the building alongside the laundries. Washing was done by hand, with the students strictly limited to twelve articles each week. From washing to fraternisation to how they spent each hour of the day, the students’ lives were tightly regimented.

The first bell rang at 7 am, telling the students to wake up, wash and dress. At 8 am, a bell rang for breakfast of porridge, toast and tea. Classes began at 9 am before stopping at 12.30 pm for the main meal of the day, typically stew and a dessert. Afternoon classes began at 1.20 pm and continued until late in the afternoon. At 6.30 pm everyone would have a small meal called supper, often just bread and jam and more cups of tea.

In the evenings, students were expected to study quietly from 7.15 pm to 9.30 pm when they would do prayers and go to bed. Lights were out every night by 10.15 pm.

Students and staff ate three meals a day together; however, not all were equal. Students were rigidly assigned to a set table, while staff ate at special tables at the front of the room, often – if newspaper reports of the time are accurate – with superior menus and ingredients.

Teaching students had every Wednesday afternoon off as well as weekends. Living at the College blurred the lines between study, residential and social; as such, there were lots of groups and activities such as cricket, football, dancing, and photography clubs. Many continued their affiliation with the College sporting clubs long after graduation. The students would go on picnics and swim in the public baths. They could walk into Claremont to watch a movie or visit the shops. If they were lucky enough to live close by, students would go home to see their families, and get a proper feed.

All students were taught geography, history, education, and Latin. Girls were taught sewing, singing, kindergarten and domestic economy, while male students were taught how to teach chemistry, physics, algebra and manual training. A primary school, ‘Prac’ was established on the grounds of the College, enabling students to simply walk next door and practice their teaching skills.

Students enrolled at Claremont College knowing that most of the teaching jobs at the time were out bush or in very remote parts of the state. Student numbers in these regional schools were so small, they usually consisted of a single classroom with one teacher responsible for all students from Kindy to high school. In what was probably a cutting-edge decision of the time, a room at Prac was built to resemble a ‘one-teacher school’, allowing College students the opportunity to practice the skills required to wrangle multiple students of differing ages and abilities.

Teachers continued to be trained at Claremont until the early 1980s, when it was absorbed into what eventually became Edith Cowan University.