School culture is always the starting point

The photo you can see with this story is a favourite of mine. It’s the day, in fact, the moment, that what I describe as ‘my life’s work’ came to fruition. It was the day I opened Rosebery Primary School in Darwin as its inaugural principal.

It was a moment that signified the middle of a steep learning journey. Before it, had come thorough and diligent planning, and after it, was to come treacherous and enthralling implementation.

I remember my words at that first assembly quite well. I spoke to the different things the 300-odd students and their families would notice about our school. We were a co-teaching school, we had a policy of not burdening students with traditional homework tasks, we were co-located with a middle school and we had no library – instead taking age appropriate resources to where the kids were learning.

So, I began with proudly highlighting difference, and therefore said my first “good morning” … differently. Instead of the standard principal fare of my greeting being returned with a slow, sombre “goooood moooorning, Mr Voigt” I insisted that our way of saying good morning would be enthusiastic and followed by two claps. I bellowed “good morning, everyone” (insert <clap clap>), and was returned a rousing “good morning, Mr Voigt” <Clap Clap>, in surprising unison.

When I left Rosebery Primary School and continued to live locally while I founded Real Schools, I discovered that none of my staff, students and families that I bumped into thanked me for my original co-teaching methodology. Nor did they care about the homework or the library absences. All I encountered was grinning representatives from all three stakeholder groups sneaking up behind me in the freezer section of the supermarket to snigger “good morning, Mr.Voigt” <Clap Clap>.

So, this photo also signifies my deep interest in school culture and the leadership of it as being central, critical even, to genuine school improvement and measurable success.

Most of us believe in school culture as being important, but when asked to define it, a distinct case of Dennis Denuto (think the lawyer from ‘The Castle”) embodies us and we start to use words like vibe and atmosphere and feel. School culture, to my mind, is best defined as a set of behaviours – those we encourage and those that we tolerate. Both, whether we like it or not, are the sum of our culture. These behaviours are enormous in number and cannot be addressed formally, although many have tried.

We’ve spent precious time identifying values that mean little more than the banners and letterheads they are spread across. But with respect as the most common of the Australian school values, why then are so many schools struggling with it? It’s behaviours that count.

In preparing for the opening of Rosebery PS, and certainly since, I’ve thought deeply about how to create a culture where the right behaviours are encouraged, celebrated and recognised, and also where undesirable behaviours are starved of oxygen. In simple terms, it’s about school leaders choosing to think a great deal more about how they are leading than what they are trying to lead.

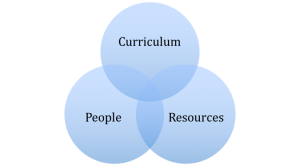

To reflect on the process of building this culture, I became convinced that I needed some guidance and structure. Having always believed strongly in the value of a model to drive behavioural consistency, I set about designing one. Knowing well that the best model for unity and balance, an obvious ambition for a new school, was a three sphered Venn diagram I thought about my three most important domains and devised this model:

Content with the balance of brilliance and simplicity of my model, I began to list the actions in each domain that would reflect my commitment to each – and then I realised my error. I was writing down only what I would do and not at all how I would do things. This model was driving the what and not the how of school leadership. Start again, Voigt.

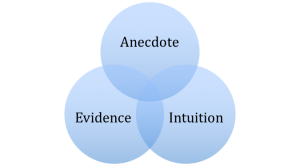

Deeper reflection about what really matters when we seek to positively influence the behaviours within our cultures led me to a different model and three entirely different domains of leadership practice:

Anecdote reminds me to think hard about context and the stories or tales that the very real people in my school community tell when they are in informal settings. I imagine myself as a fly on the wall at dinner tables, barbecues, campfires, supermarket queues, hairdressers and especially in my own car park and staff room. I became determined to impact the quality of these conversations and to have them positively framed by the positive interactions that all stakeholders in the school experienced, every single day. Anecdote, therefore, is more than story. It’s about the depth and quality of the relationships we’re cultivating at school.

Evidence is about proving the effectiveness of our work. No school leader should adopt another program or embark on another action cycle without clear determination to prove the value, or otherwise, of that venture. As Professor John Hattie reminds us, “know thy impact.”

Intuition connects to a very clear and desirable future skill – that of cognitive load management. In effect, it’s about not just finding information but knowing which sliver of the vast information tracts available to us is relevant. Further, this is about using the right knowledge to challenge convention and tradition. We need more school leaders willing to do just that.

Models like these though, are tools of reflection – and not accountability. Nobody at Rosebery Primary School knew of my model. I didn’t need it being used for judgement or for appraisal. It was for me. I could reflect using it, by plotting my work, my defaults over periods of time ranging from a conversation to a semester.

My model was not about perfection or about feeling bad if I wasn’t perfect. It was about adjustment and small steps. Mostly it was about behaviour; the very foundation of school culture.

Finally, I encourage you to build your own model and to avoid the temptation to steal mine. Sure, reflect upon it and weigh its relevance to you, but know that my model was for opening a new school – which is unlikely your current challenge.

Model theft is the easy way out. Designing your own – for your own place, your own challenges and your own future aspirations – might just be the most powerful thinking piece you can embark upon.