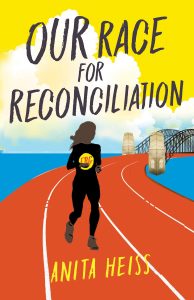

It’s NAIDOC Week. I wasn’t sure how to mark it, what to offer, what to write about for my newsletter, so I decided to review Anita Heiss’ youth audience (YA) novel, Race for Reconciliation. I read it in one sitting. I couldn’t stop.

Anita Heiss is an Indigenous Literacy Day Ambassador and a proud member of the Wiradjuri nation of central New South Wales. She is a writer of non-fiction and fiction, including poetry, and is among those whose writing has changed the way I see the history of the land upon which I walk.

I’m an immigrant. I was born in England, and brought here at age three with my whole family. I grew up in Darug Country, on the tribal lands of the Bediagal people. I’m a parent and have been a teacher. My only right to speak on Indigenous issues is that the book was sent to me for review. I have an Irish-English white voice, but this voice is the only one I have, so this NAIDOC Week, I will use I to say what I have learnt.

I imagined it would be a book about role models and identity – about a young Indigenous girl, Mel Gordon, who is inspired by Cathy Freeman to aim high and take gold one day, literally. Knowing a little of Heiss’ other writing, I should have realised it was going to be so much more.

I read this novel against the backdrop of the recent furore following a teacher’s decision to teach the history of the Stolen Generations through panic. Year four students were informed that they were to be removed from their parents’ care that afternoon, under the orders of the prime minister.

Natalie Whykes told the ABC that her son Kynan, who attends St Justin’s Catholic Primary School in Oran Park, remains confused and anxious about being stolen.

“One of the sisters came in with an envelope and the kids were told that this was a letter from Malcolm Turnbull saying they were being taken by the school and weren’t going to see their parents again,” she told the ABC.

The lesson had been used the year before. The teacher in question seemed to know the value of narrative for educative purposes. The unit involved a book called Stolen Girl written by Gugu Yalanji author, Trina Saffioti, whose grandmother was a victim of the Stolen Generations, illustrated by Norma McDonald of theYamatji and Nyungar peoples.

“I just feel like it sort of cheapens almost what has happened with the Stolen Generations — I feel really uncomfortable with that approach,” Saffioti told the ABC. She’s not alone.

Edith Wright, from the book’s Broome-based publisher Magabala Books told the ABC it was important for schools to speak to survivors of the Stolen Generations and their descendants: “The lesson is, if you’re non-Indigenous, seek out an Indigenous person to get some advice on how to handle such a sensitive subject.”

Now, there’s an idea.

There’s much to be learnt from a story, and the writing of Indigenous authors is enough, just as it is. Perhaps there was an underestimation of the children’s empathic capacity? In my experience, explaining what happened and telling or showing stories is enough to bring tears of sorrow to young eyes, and those of the teachers. Fear is not required.

So how to teach about the Indigenous experiences after the arrival of white people on these lands? How to explain how the effects reverberate like a ripple across an inland sea -generation after generation – passing a legacy of pain, dislocation and shame, inherited in place of the stories and connection to Country of their birth right?

Story telling is one of the BEST ways to learn, and this reading taught me so much. Heiss’ book transported me to my own primary school days. It nudged at the inherent desire to ‘belong’ that all children feel. This fear of rejection and ‘othering’ never fades completely. As I read, I was relating; I was identifying. I was gaining understanding of what it means to be considered ‘not black enough’, or ‘too white to be black’ – judgement and identification from the external gaze.

I found myself getting exciting when I realised that an Indigenous voice was about to give me the right words to explain to a child why ‘black face’ is a problem. Setting these lessons in the classroom, and letting the student characters speak their minds, Heiss has provided Australian teachers with a pedagogical gem.

It’s not just the pain that is depicted either, but also the strengths of the First Nations people. And they are MANY. I learnt about how Indigenous parents brush aside the sting and imbue their kids with pride and grit. This book tells me family is a formidable strength in Indigenous cultures. They constantly fortify their children with a culture of love, forgiveness and integrity. “Don’t hit, just outwit,” Mel and Sam have been taught.

Back to the classroom: It’s May 26, 2000. Sam (Mel’s twin) and Mel’s teacher, Miss C with her “white toothpaste smile”, has written ‘Sorry’ on the board. She’s ready to explore the functional and ethical parameters of an apology with her students. The topic is deftly addressed with both sensitivity and solemnity, yet…

“Why are you sorry Miss? You didn’t do anything,” says George, who acts as a microcosm for ignorance and prejudice throughout.

“No, I didn’t, George, but sometimes we say sorry because we feel bad about other people’s suffering,” she replies.

Fast forward to NAIDOC Day. Mel and Sam turn up at school wearing the colours of the Aboriginal flag, ready to celebrate NAIDOC Week and welcome Cathy Freeman to their school. Mel realises that quite a few kids are missing. Worried there is an epidemic afoot in their small and intimate school, she asks Miss C about it. Miss C’s famous smile dims. She stalls. George Smith interjects, swallowing her silence with his customary lack of sensitivity. He announces it’s because their parents don’t think they should be celebrating NAIDOC Week.

We’ve come so far with Mel. We’ve fallen head over heels in love with Nanna Flora who was stolen as a child and won’t stop loving all her pain and sorrow away. We know why “Queen Flora” must be cherished and not lift a finger at the Gordon house. We’ve been to a Sydney march bigger than the anti-Vietnam war rally, and now this. George again.

At least he’s there, I guess…. “My parents like Cathy Freeman, so they’re glad she’s coming to visit. But she’s a sportsperson and that’s better and more important than being an Aboriginal isn’t it, Miss?” Miss C brings home gold with “she will retire from running one day, but she will always be Aboriginal, so that’s more important than being a sportsperson. And being Aboriginal is who she was when she was born.”

The lessons are there for the asking. It’s just a matter of asking for input from those who have a right to talk on it.

Reconciliation Australia provides resources for teaching and learning

Narragunnawali supports all schools and early learning services in Australia to develop environments that foster a higher level of knowledge and pride in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and contributions.

Narragunnawali supports all schools and early learning services in Australia to develop environments that foster a higher level of knowledge and pride in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and contributions.

Narragunnawali (pronounced narra-gunna-wally) is a word from the language of the Ngunnawal people, Traditional Owners of the land on which Reconciliation Australia’s Canberra office is located, meaning alive, wellbeing, coming together and peace.