John Hattie: why I support the education minister’s teacher education review

Last month, Federal Education Minister Alan Tudge launched a six month review into teacher education.

The review aims to attract and select high quality candidates into teaching and prepare graduates to be more effective teachers.

The announcement was met with criticism from many in the sector. Some education experts have said the review’s focus on teacher education is too limited. Others found it offensive of the minister to suggest Australia’s teachers are not already effective.

But the review is necessary. Its focus complements and adds to the previous review into teacher education in 2014.

What’s happened since the previous review?

In 2008, prominent education academic William Louden noted there had been around 101 reviews or inquiries into teacher education since 1979. It’s understandable then, why many people believe another is unnecessary.

But the current review’s terms of reference don’t double up on the last review, in 2014. In fact, they continue its progress.

The Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group was put together in 2014 to review teacher education with a focus on student outcomes. Its report’s title Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers summed up the mission.

Since then, many universities offering teacher education and organisations such as the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) have been engaged in implementing the report’s 30+ recommendations. These include:

a review of accreditation standards for teacher education programs. (The revisions to the standards occured in 2015, with further updates made in 2018 and 2019)

ensuring higher education providers select the best candidates into teaching courses. (Guidelines were agreed to by all Australian education ministers in September 2015 and a document developed by the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership)

for course providers to use a national literacy and numeracy test to demonstrate all pre-service teachers are in the top 30% of the population in personal literacy and numeracy. (The Australian government instituted the Literacy and Numeracy Test for Initial Teacher Education Students (LANTITE in 2016)

improved data on teacher supply and demand (The AITSL now hosts the Australian Teacher Workforce Data (ATWD), which connects data on teacher education and the workforce around Australia. Its first report came out in 2020)

help for graduate teachers starting their careers (such as AITSL’s My Induction app)

for course providers to equip all primary student teachers with at least one subject specialisation, prioritising science, maths or a language. (This became part of the accreditation standards for teacher education programs. AITSL requires course providers to publish specialisations available on their websites and report numbers of commencing, enrolled and completing graduates per specialisation annually).

Improvements such as those above can be credited to deans, teacher registration boards and education staff.

Overall, teacher education is improving. In Victoria, where the minimum ATAR to get into teaching has been 70 since 2019, average ATAR scores have risen. The percentage of students and school principals who argue graduates are well prepared for teaching has increased, and the number of teacher education programs across Australia has dropped (to 359 — a decrease from 425 in 2013).

We do have excellent teacher education programs across Australia. The aim now is to make more programs attain a high level of excellence.

Why we need this review

Despite what many critics and pundits may say, the current review is not a review of teaching in general. Rather, it’s specific to some of the issues that have arisen out of the implementation of the 2014 TMAG report.

One example of such an issue is how universities assess their student teachers as classroom ready.

A major recommendations of the 2014 review was for the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) to develop a national assessment framework to help universities assess the classroom readiness of student teachers throughout the duration of their program.

The teaching institute did promote teacher performance assessments (or TPAs) which require student teachers to collect evidence of their positive impact on students during the final term of their study.

Universities must have their TPAs reviewed by an expert advisory group to ensure the quality of these is consistent across providers. While many universities have had their teacher performance assessments reviewed, some have yet to do so.

The first half of the current review attends to issues of classroom readiness — particularly improving the teacher performance assessment process. It asks about the extent of evidenced-based teaching practices in the teacher education programs.

It invites discussion on how student teachers can get practise in schools (COVID highlighted some of the problems) and how school staff play a greater role in developing teacher education programs (and help reduce first year of teaching shock for some).

It also asks how teacher education providers can play a stronger role in ongoing professional development and support of teachers.

The other half is about attracting and selecting high-quality candidates into the teaching profession.

In 2017, the average age of starting a teacher education course was 23-29, so many come as a second career.

Giving up two years of earnings is a high price to pay, so finding ways to make programs attractive needs debate, as does ways to entice high performing and motivated school leavers to choose teaching as a career.

Teaching is a hard career to move into for mid to late career professionals. The announced review asks if there are ways to make this transition more feasible.

Almost half the students who enrol into teaching programs don’t complete their course (about 30,000 enter each year and 18,000 complete). Of the students who started an undergraduate teacher education program in 2012, 47% had completed their study after six years (the length of an undergraduate course is usually four years full time).

There is little evidence on who drops out and why.

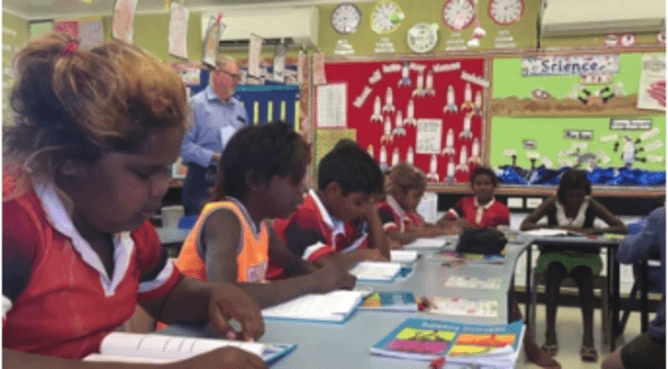

The teacher workforce in many schools is mostly female and white. This does not reflect the school population. Are there ways we can attract a more diverse cohort into studying teaching so teachers better mirror the diversity in school and society?

The review aims to answer these questions. It’s a critical enquiry, aiming to build on the success teaching educators have built over the past seven years. It is focused, addressing unresolved issues from the last review, and it deserves submissions from as many people as possible representing a broad range of views.

We have a chance to be proactive, scale up success, and promote the high quality teacher education programs across Australia.![]()