If we want brilliant English, history or geography teachers, why are we making humanities courses so costly?

The government’s university funding reform package passed the lower house in early September and will pass the Senate if the Coalition succeeds in garnering enough crossbench support.

The plan would see fees for some humanities degrees rise by as much as 113%, while fees for courses in fields such as teaching, nursing and STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) would drop.

Education Minister Dan Tehan has said the bill aims to create more “job-ready” graduates, including teachers. But undergraduate education only degrees aren’t the only way to create brilliant teachers.

There’s no doubt demand is high for teachers with expertise in STEM subjects such as maths. But students also deserve expert English, history, civics or geography teachers too. Perhaps your favourite teacher at school did an arts or humanities degree, especially if they taught in one of those subjects.

An under-discussed aspect of the government’s proposal is it risks pushing many would-be teachers in these fields away from undergraduate humanities training, potentially at the expense of their future students.

Producing excellent teachers

We all know what makes a great teacher — someone who loves what they are teaching (their discipline) and is passionate about engaging students.

Research from the University of Melbourne suggests there is rich relationship between the teacher as a person and their teaching practice, which includes their subject knowledge. The attributes of effective teachers include personality, cognitive capability, self-efficacy (belief in one’s ability to get the job done), communication style, motivation, cultural competence and self-reflection, the researchers found.

But as anyone who has met a brilliant teacher can tell you, passion for the subject matter is also crucial.

If we want teachers (particularly secondary teachers) to know and love their subject, and we want brilliant English, history or civics teachers, why make it so costly for them to gain deep background knowledge in the disciplines they’re destined to teach?

What do teachers study at university?

There are commonly multiple routes into teacher education: one via a dedicated Initial Teacher Education (ITE) degree (typically a Bachelor of Education) and another via a postgraduate ITE degree (typically Masters of Teaching). However, a double degree, one that invites depth in both subject matter and educational expertise, is becoming increasing popular.

Research published in 2011 by the Australian Council of Educational Research said

Overall about 29% of primary teachers hold a qualification in a field other than Education, as do about 57% of secondary teachers […] The difference between primary and secondary proportions is mainly due to the fact that secondary teachers are more likely to complete a degree in an area like Arts or Science before undertaking a graduate qualification in Education.

In other words, many current teachers have arts degrees and current students are reaping the benefit of this in-depth knowledge.

In the almost 50 countries that contributed data to the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey in 2019, discipline knowledge took up the largest amount of initial teacher education, followed by pedagogy and classroom practice. Interestingly, across these OECD countries, teaching was the first-choice career for two out of three teachers.

The 2014 report Mapping the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences in Australia noted there were

[…] current debates regarding the importance of school teachers having substantial disciplinary backgrounds in the subject area they are destined to teach, rather than merely training in education […] data implies that there may be as little as 18% of the degree programme available for developing a disciplinary background in a [Field of Education or FOE] other than Education; if that is indeed the case, it would be hard to argue that this enables the acquisition of a substantial disciplinary background in another FoE.

That same report said:

In 2011 Education students received 82% of their teaching from the Education FoE, with the largest service teaching component coming from Society and Culture (9%). As noted earlier, this is much lower than one would expect or is desirable if, for instance, prospective high school teachers are expected to have majored in the discipline they wish to go on and teach.

Inspiring teachers

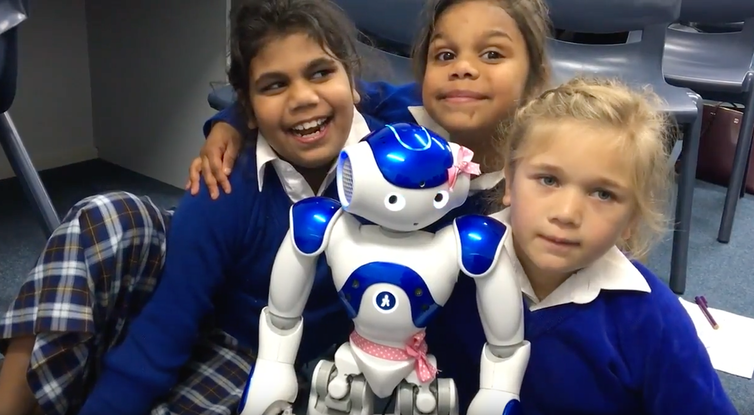

Did you have an English teacher who studied literature, and imparted their love of it to you? Or a history teacher who brought stories from the past to life, because they’d studied them in depth as a history major? Perhaps you remember a geography teacher who instilled in you deep curiosity about culture and geopolitics, because they majored in this field at uni.

Doesn’t the next generation of school students deserve the same?![]()