Funding for schools will increase by $18.6 billion over the next decade, but there are winners and losers. The Catholic Schools are set to lose substantial funding and a list of 24 elite independent schools will also take a funding hit. Read on for a summary of the 2017 education budget.

The government is set to save A$2.8 billion over the five years from 2016-17 by reforming the higher education system. This includes a 2.5% efficiency dividend on the Commonwealth Grant Scheme in 2018 and 2019, and a 1.82% annual increase in student contributions to the High Education Loan Program from January 1, 2018 (a 7.5% increase over the forward estimates).

The minimum income to start repaying HELP debt will be lowered to $42,000. The repayment rate will increase with income, from 1% at the minimum threshold to 10% at A$119,882, the maximum threshold.

The government will save $181.2 million over the forward estimates by limiting eligibility for VET student loans to certain courses.

School funding

Louise Watson, Professor of Education at the University of Canberra:

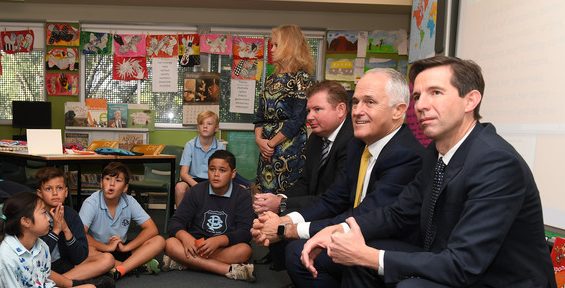

By retaining the architecture of the Gonski model and promising funding increases above inflation for the next three years, Malcolm Turnbull has taken Coalition schools funding policy back to the sensible centre.

To dispel any doubts about the government’s commitment to bipartisanship, David Gonski has been reappointed to advise on fine-tuning the system dubbed Gonski 2.0.

In all, 24 schools – mainly Independent schools in Canberra and northern Sydney – have been deemed “overfunded” because their income exceeds the Schooling Resource Standard (SRS). Although they can expect reductions in funding over the next decade, $40 million is available for “adjustment assistance” to schools experiencing unreasonable hardship in the transition.

The government will give $125 million over five years to private school representative bodies in the states and territories to support “the implementation of the government’s reform agenda”.

Commonwealth capital grants for private schools will increase by 28% to an estimated $182.5 million per year in 2021.

Students considered disadvantaged will attract additional funding. A “location loading” will increase funding over the decade to schools in regional and remote areas by 5% per student per year, compared to the national average of 4.1%.

Funding for Indigenous education and for schools in the Northern Territory will also increase. Pre-school funding will increase by $429.4 million in 2018. New funding rates for students with disability are anticipated in 2018.

The government’s stated aim, in promising an additional $18.6 billion in schools funding over the next decade, is to bring federal funding for government schools to 20% of the SRS and federal funding for private schools to 80% of the SRS by 2027.

The SRS – to which federal recurrent funding is linked – will be increased at a fixed rate of 3.56% per year between 2018 and 2020. Thereafter, the SRS will be adjusted in line with a floating indexation rate that reflects “real changes in costs”. So from 2021, federal schools funding will be influenced by what costs are included in the SRS index and how much they change.

University fees and cuts

Gwilym Croucher, Senior Lecturer in the Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Melbourne:

The government has confirmed the package of changes it announced a week ago with significant cuts. Students in particular will pay more, a lot more.

Student contributions will increase by 1.8% each year between 2018 and 2021 for a total 7.5% increase. This means they will pay 46%, instead of 42%, of the cost of their degree on average.

So, for a four-year course, this is an increase in total student fees of between $2,000 and $3,600. The government claim the maximum any student will pay is $50,000 for a four-year course, and $75,000 for a six-year medical course.

Apart from yearly indexation, this fee rise is only one of a few major increases since the ALP reintroduced fees in the late 1980s and will be smaller than the last time.

While few students will welcome the increase, the evidence from previous fee hikes in Australia is that it will not deter many people from study.

However, when combined with the lower HELP thresholds for repayment and higher repayment rates, the changes may make studying less attractive than in the past, and potentially prohibitive for some students.

Universities too will suffer a direct cut of $384.2 million over two years. This will come in the form of an “efficacy dividend” to the Commonwealth Grant Scheme of 2.5% in 2018 and another 2.5% in 2019.

While no university will go broke from the efficiency dividend, it forms part of a series of cuts. Combined with the changes to how grants are indexed, there is little doubt universities will receive less per student in subsidies in the future, and will have to do more with less.

The package averts the worst cuts from the previous minister’s attempts to deregulate higher education, but offers little in the way of a long-term vision to students or universities.

HELP student loans

Bruce Chapman, Professor of Economics at the Australian National University:

Budgets are always contextual and reactions to them will always be relative to alternatives.

The natural comparison of the 2016/17 changes to HECS-HELP is still the extraordinary 2014/15 budget plans of the previous education minister, in which there were to be initial outlay cuts of around 20%, the introduction of a real rate of interest on HELP debts, and the introduction of the facility for universities to charge any fee they chose. If that was a man or woman-eating crocodile, then this budget is a pussy cat.

For HECS-HELP, there is to be an increase in charges introduced over a three-year period, maxing out to 7.5%. This is not a big deal and will not affect student or graduate debt; in effect it will add about a year to how long people have to repay.

More significantly, the first income threshold of payment is to be reduced from the current level of about $55,000 a year to a new and much lower level of $42,000 a year.

But, importantly, the rate of collection of the debt will be cut as well, from 4% to 1% of income. This will mean that the effect on the majority of debtors will be small.

Most affected will be current part-time workers, and the increased obligation essentially means a faster rate of repayment, and not a major impost.

Changes to VET

Kira Clarke, Lecturer in Education Policy at the University of Melbourne:

Treasurer Scott Morrison framed his announcement of a new fund for skilling Australians by saying “skilled migration must be on our own terms”.

Appealing to public animosity towards a perceived reliance on skilled migration, the treasurer announced a levy on employers of foreign workers employed under a new temporary skill shortage visa.

Employers will be charged between $1,200 and $1,800 per worker employed under this visa scheme. It is anticipated this levy will contribute to $1.2 billion within the Skilling Australians Fund.

States and territories will be able to access the fund for the explicit purpose of supporting up to 300,000 apprenticeship, traineeship and higher-level skilled workers.

The treasurer’s language in announcing this new pot of money appeared to put the onus on states and territories to stimulate apprenticeship and traineeship opportunities.

Apprenticeship commencements have been in decline, particularly in trade occupations.

This decline is part of a long-term trend, and is compounded by the impact of the gig economy and the reluctance of employers and young workers to enter into four-year training relationships.

Part of a suite of announcements aimed at “Backing regional communities”, the budget also includes $24 million for Rural and Regional Enterprise Scholarships.

The budget papers indicate that scholarships will be available for up to 1,200 students, to support skills development and educational attainment.

While it is unclear whether $15.2 million allocated to establish eight regional study hubs in rural and remote areas will include enhanced access to VET, any increased access to VET programs for regional learners could be a positive step in addressing youth unemployment and lower educational attainment in regional areas.

This article was written by Louise Watson, Professor and Director, The Education Institute, University of Canberra; Bruce Chapman, Director, Policy Impact, Crawford School of Economics and Government, Australian National University; Gwilym Croucher, Senior Lecturer, Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Melbourne, and Kira Clarke, Lecturer, Education Policy, Centre for Vocational and Educational Policy, University of Melbourne. The article was originally published on The Conversation.

This article was written by Louise Watson, Professor and Director, The Education Institute, University of Canberra; Bruce Chapman, Director, Policy Impact, Crawford School of Economics and Government, Australian National University; Gwilym Croucher, Senior Lecturer, Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Melbourne, and Kira Clarke, Lecturer, Education Policy, Centre for Vocational and Educational Policy, University of Melbourne. The article was originally published on The Conversation.