The Vital Role of the Arts in Schools: A look at artists-in-residence

Programs that facilitate artist- and writers-in-residence are currently not widespread in Australian schools, but the benefits of such opportunities are extensive, far beyond simply teaching individual students to write or paint, extending to teaching staff, the school community as well as the broader arts sector.

“Art is an important form of self-expression,” says author Dee White. “It makes students more observant because they are encouraged to look around them to find sources of inspiration and solutions to creative problems.”

“Many children who are not the best at sport [or academics] engage well with visual art. I have witnessed over and over, the wildest of children becoming calm when engaged in art,” adds artist Tricia Stedman. “A good visual art programme will encourage children to be inquisitive and they will learn many things through developing their observation skills.”

Both White and Stedman have been engaged as artists-in-residence at Australian schools; White most recently as the 2020 Author in Residence at Yarrawonga College in regional Victoria as part of the Creative Learning Partnerships Program, and Stedman as Artist in Residence at multiple West Australian schools across the metropolitan area and remote communities.

“An artist or writer-in-residence provides a completely different perspective for students both in relation to learning and to the creation of their own work. It can also provide staff with fresh tools to engage students,” says White.

The benefits of artists-in-residence

An artist-in-residence is a role where an established creative – writer, artist, poet, musician, game developer, animator or performer – spends an extended period of time in a school community, working with students and staff on individual, class or school-wide projects.

The goal of the residency will vary, from demonstrating basic art skills in schools that have never had a regular art teacher to publishing anthologies of written work. But the outcomes are much greater.

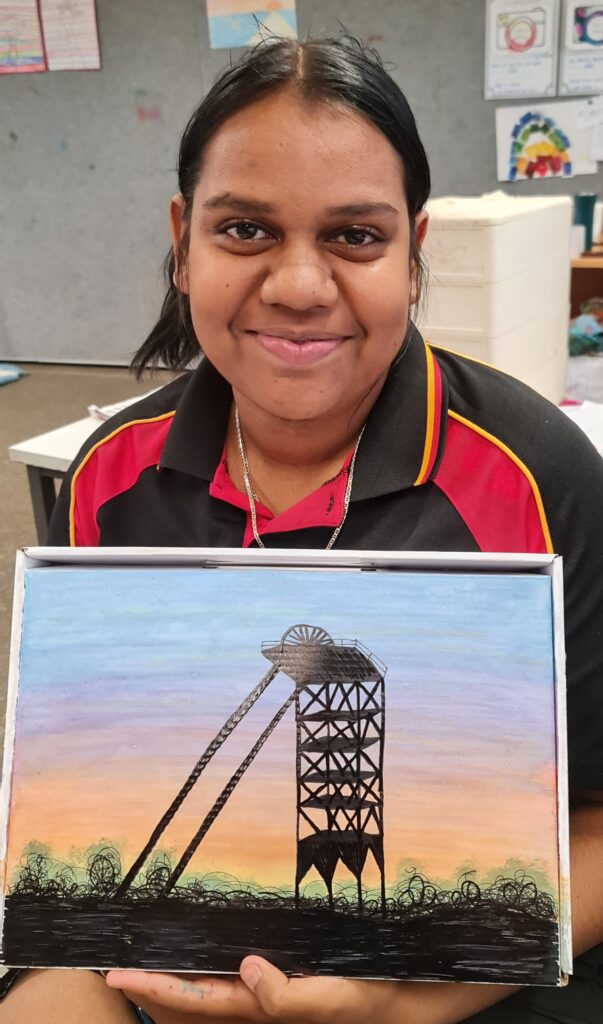

“As an artist-in-residence you are helping others to find their voice and their own creative spirit,” says Stedman. “But over the period of the 4 weeks of the programme there were huge improvements in the behaviour of all of the students and classes across the school. There were students who would not engage at all to start with, and yet these students can be seen in the photos taken at the end of the programme, holding their artwork and smiling proudly.” Stedman also said there were improvements in attendance rates and engagement from students during the residency.

White also saw a significant change in the attitude of students across the school. “It enhances students’ problem-solving skills as they solve problems for their characters, and work out how to tell their stories or express their art in a way that’s most meaningful to them… The creative process is good for elevating mood and helping students feel positive about themselves [and it] can bring pleasure to students of all abilities. I’ve worked with students in a special school who weren’t able to write, but using paper finger puppets, they were able to create verbal stories that they were extremely proud of.”

As part of her month-long residency at Yarrawonga College, a school of 700 students from P-8, White worked with students from all year levels to create stories based on their experience of living in a rural town, using their culture, heritage and surroundings as inspiration. “The theme of the artist-in-residence project was Our Story is Your Story. It supported students to tell their stories no matter what their background or circumstances and to realise and own the fact that their story was just as important as anyone else’s.”

“Art gives students a chance to express themselves and be heard. It also enables them to walk in the shoes of others and broaden their understanding of themselves and the world around them.”

But it wasn’t just students who developed new skills from the program.

“During the project I also conducted staff PDs and provided information about alternate ways to teach writing and engage students in the writing process. I also shared some resources and strategies to inspire both reluctant and able writers,” says White.

Kathleen Hodgson is the Senior Arts Officer with Creative Victoria, the department in charge of the Creative Learning Partnerships program which funds creative professionals such as Dee White to undertake residencies in Victorian schools. She says there are a number of positive impacts on the wider community:

“When parents learn there is a creative-in-residence at a school, they are curious… and want to know more. The broader school communities feel they too have permission to get involved. For example, at a primary school in regional Victoria, the postman volunteered to help students collect data from residents about sightings of birds they were researching in their project. In other projects, community elders have been invited to be interviewed and become part of students’ storytelling. Creatives and schools are often enthusiastic to engage with local First Peoples as a foundation of their project concept, and consult subject matter experts like ecologists, scientific researchers, or historians to add to the collaborative practice common to creatives.”

“Recipients have told us that the program has changed the landscape of their schools, and had positive impacts on the wellbeing of staff and students. One school reported that its creative project changed the entire school’s environmental program and incorporated art into its broader curriculum. [They] also reported that the program boosted teacher confidence – and that it was a ‘school changing’ opportunity.”

Funding creatives in schools

The Creative Learning Partnerships is Creative Victoria’s longest-running grants program and has been funding artists and creatives in Victorian schools for four decades, bringing more than 1,500 creatives to over 1,200 schools. Unfortunately, not all states have similar programs.

Funding opportunities vary from state to state and often depend on schools chasing up partnerships and grants.

“Remote and/or disadvantaged schools sometimes receive additional funding from the Department and this will allow the school the opportunity to develop an artist-in-residence programme,” says Stedman of her work in Western Australia. “In some instances other government departments such as the Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries team up with not-for-profit groups such as Lotterywest Creative Communities to provide funding for projects that engage the school and communities. Other NFP’s such as Form or Awesome Arts also sometimes set aside funding for artist-in-residence programmes in schools.”

White said she had done residencies that were funded by local and state libraries, with students travelling to the libraries for the sessions. “Funds can also be raised through Parent Teacher Associations and organisations like local banks (eg Bendigo Bank) and councils. Community groups might also be able to provide funding for an artist-in-residence.”

However, until there is a national focus on, and funding for the arts, the ability of schools to engage in an artist-in-residence program will depend highly on individual effort and enthusiasm.

Bringing Arts Back in Focus

“A nation with a strong cultural policy is a nation where we know ourselves, know each other and invite the world to better know us,” declared the new Arts Minister Tony Burke in a speech to the Arts Industry Council in 2021. “Cultural policy is more than some funding announcements for the arts. When you get it right, it affects our health policy, our education policy, our environmental policy, foreign affairs, trade, veterans’ affairs, tourism1.”

Since 2013, Australia has been no formal national cultural policy and a significant reduction in funding for the arts. A restructure in 2019 saw the arts portfolio subsumed into the newly created Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications. The same government department responsible for writing policies about vehicle noise and urban irrigation was making funding decisions about arts festivals and cultural heritage.

It was only after the Federal election in May 2022 that the ‘The Arts’ was added back into the formal name of the department, now the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts.

The Arts Minister has promised a new National Cultural Policy which is to be developed in consultation with multiple artistic organisations from across the country. Across the sector, it is hoped that the new policy puts the arts at the forefront, with schools included in the spotlight.

Kathleen Hodgson of Creative Victoria, says “Student engagement in the arts can help improve educational outcomes by boosting motivation and creativity, building confidence and self-esteem, leadership skills, cooperation and collaboration as well as forging friendships and a sense of belonging. Creative learning builds students’ capacity to undertake critical and creative thinking, a vital life skill to assist them to effectively respond to environmental, social and economic challenges ahead.”

References: