‘Just say no’ doesn’t work for teen sex and drug use, so why rely on it for young driver education?

Human behaviour is complex. And yet approaches to road safety education are commonly far too simple, especially for young drivers. They are not only inexperienced but also biologically wired to be among those most at risk of crashing.

It is time to explore a new, more proactive approach to driver education.

Currently, we focus on teaching young people about major crash risks. Then we tell them not to take those risks. Should we really be surprised this does little to reduce the problem?

Common risks for young drivers include speeding and driving while tired. They are also more likely to be distracted by mobile phones or an array of other secondary tasks that take their eyes – and minds – away from the road.

Young drivers are not alone in taking risks. They see them on the road every day, often among their own family members and social circles, which normalises such behaviour. However, coupled with their lack of experience, such risks are much more likely to result in a crash for the young driver.

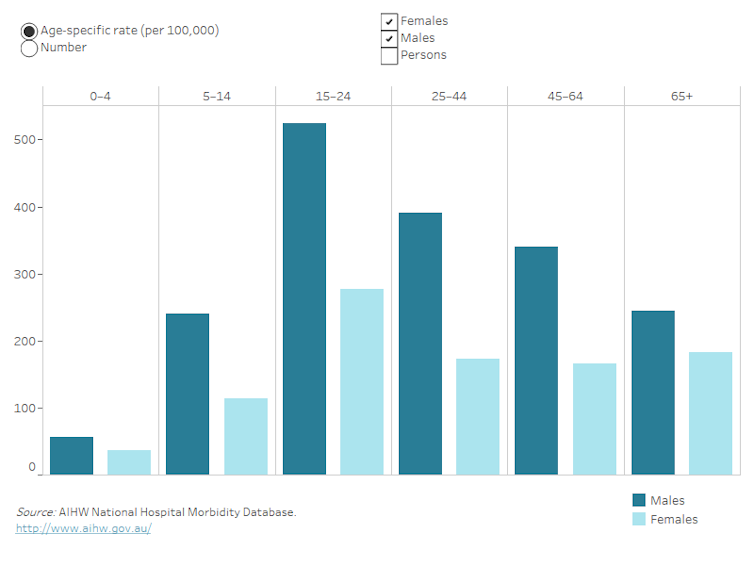

Transport accident hospitalisation rates are highest for young drivers

Is it realistic to expect we can predict and plan ahead to never become fatigued while driving? How many of us refuse all phone use while driving? In today’s highly connected world, why do we expect this of young drivers?

Why then does youth road safety education often simply adopt a “just don’t do it” message?

Some risks are inevitable

In other fields of youth health, education has long moved on from such an approach. It has progressed to teaching young people strategies both to avoid taking risks and to reduce harm if the risk does occur. Some risks are even considered inevitable.

An example of such a shift in approach is the move from “just say no” to safe sex education around the 1970s. Some feared this would lead to young people having sex earlier. Not only were these concerns unfounded, but research continues to show a link between sex education and lower rates of teenage pregnancies.

This approach is known as risk or harm reduction, or minimisation. It is well recognised in relation to risky alcohol and other drug use. Think of needle exchange programs, safe injecting rooms and, more recently, pill testing. Initiatives like these receive mixed support but are shown to reduce harm.

Harm-reduction approaches are evident in many other road safety measures that allow for margins of error. These include demerit point systems for offences and vehicle technologies that activate only after a certain threshold is exceeded. These include speed alerts, seatbelt reminders, feedback to stay inside the lane and phone-blocking apps.

In fact, allowing for human-made risks is a tenet of systems engineering. If risk can’t be eliminated, then systems are re-engineered to at least transform or reduce the risk of harm to an acceptable level.

How would harm reduction work for young drivers?

Many experienced drivers compensate for risky driving conditions by slowing down and leaving a greater gap to the traffic ahead – even if they don’t consciously realise this.

There is clear, physics-based evidence these compensating behaviours reduce crash risk. The result is a wider view of the road environment so drivers can see any potential hazards early. They also have more time and space to react to any hazards.

A harm-reduction approach to driver education would still emphasise avoiding key risks. However, it would also challenge young people to reflect on their own “inevitable risks”. Will they never be tempted to speed when running late for work? Will they obey every road rule, even when they see others breaking them? Would any of their answers be different if certain friends or family members were their passengers?

If not able to eliminate the risk, young people would be challenged to identify strategies they would be willing and able to apply to reduce potential negative consequences of the risk. Slowing down and increasing following distances are key responses to many risks.

Other more tailored options include interacting with a phone only while stopped at traffic lights rather than when moving – albeit still teaching that this is not risk-free.

Time for a fresh approach

Some might argue harm-reduction approaches to driver education are too risky. We know the casualties in young driver crashes are more often their passengers or other road users rather than the young driver. However, we also know road risks cluster with other youth risks and harm reduction works to reduce negative outcomes from these other risks.

Current approaches are not working, or at least not well enough. Young drivers remain persistently over-represented in road trauma statistics, despite decades of attention. Without any evidenced-based research on harm-reduction approaches to road safety, the potential benefits as well as risks remain unknown.![]()