Teaching, learning and culture at Tennant Creek

Teach For Australia (TFA) is part of Teach For All – a global network of over 40 independent, locally led and funded partner organisations with a shared vision for expanded educational opportunity.

Each organisation recruits and develops diverse individuals from a range of academic disciplines to commit themselves to teaching for two years.

In Australia, these ‘associates’ are placed in schools with a high level of need for transformation, due to disadvantage. TFA ‘partner schools’ are in the Northern Territory, Western Australia, ACT, Victoria and Tasmania – with a plan to expand to other states.

These schools find attracting and retaining staff a challenge. Will Lutwyche was an associate with the 2015 cohort and was placed at Tennant Creek, in the Northern Territory. Five hours from the closest major town, Tennant Creek is a unique place, rich in culture, but like many schools in the NT, it struggles to retain teaching staff.

Will was also one of the teachers featured on recent SBS documentary, Testing Teachers; he spoke a little on the show of the uniqueness of working with the multilingual and multicultural Indigenous student population at Tennant Creek. School News caught up with him to hear a little more about his time at Tennant Creek.

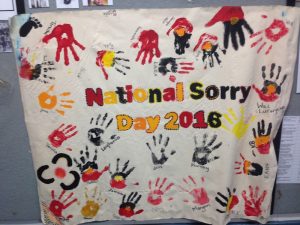

SB: There was a brief segment in episode one about teaching local Indigenous history, regarding the Stolen Generations. It was mentioned that you had redesigned the course to suit the students. Why did you do that, and how did it feel having to ‘teach’ this content to a class of students whose connection with these events was so real?

WL: I didn’t really teach the content to them so much. It was more like we were learning together in many ways, which was great. I was interested in using culturally relevant pedagogy and when we started talking about these things in class, although it was difficult for some students, they could relate to it. Many of them had heard about Indigenous rights and everything that goes along with it, but they had never had the opportunity to talk about it, particularly with a non-Indigenous teacher.

It was great to tap into that and give them my own perspective. I got to understand their stories as well. In the end their stories really drove the history unit, along with the stories of community members. It was more relevant and integral to their lives, and their families and the town of Tennant Creek. They engaged well with it and started to reflect deeply and use critical thinking, which is not always easy to do without relevant content.

I knew that in most transformational classrooms, students and teachers wrestle with injustice and discussing topics like prejudice and expectations related to things like race, class, sexual orientation, and learning difficulties comes up. I wanted to be a teacher that could provoke learning on the local and cultural histories of oppression that many students had experienced – and do it in age appropriate ways – to question the racism that had existed for so long within Australia and that community. I had done a lot of research into culturally responsive teachers, but I didn’t know what it looked like in a classroom. It’s very easy to say I want to have a culturally responsive classroom but to know what that looks like was a bit more difficult than I thought.

SB: That involved a whole range of things, didn’t it? From simple things like acknowledging the traditional owners before a class to honouring the diversity within Aboriginal culture with an identity map of their language groups and moieties. (see fig 1). Can you give us a few other examples?

WL: Getting community members in to share their stories and have ‘yarning circles’ was effective. I got kids to do some family tree stuff; they ran a lesson, which was something they’d never done. I also found some great local resources that hit the curriculum points really well.

SB: Are we talking about human resources here?

WL: Both, I found some great written resources that you had to delve deep in different books to find, and a ABC DVD called Coniston about the Coniston Massacre, just south of Tennant Creek.

SB: You had some big moments there with the students, didn’t you? In fact, it was a 10-week-long program, with depth and complexity that Testing Teachers didn’t really convey.

WL: Yes, a student found out through learning about Coniston that her great grandmother was a killed in the massacre. That kind of stuff is powerful. It gave them a point of reflection – it was a good modern resource that kids could engage with.

SB: You had to vary your responses to behaviours in class a fair bit. You talked about needing to relax a little. Which factors in the students’ lives made this necessary? Are they specific to Indigenous kids do you think?

WL: I was in my second year when the show was filmed so I’d already had a year to process and understand why certain kids had issues. I did a lot of reading on trauma-informed teaching. Calmer Classrooms is a great resource that I used quite a bit in my classrooms.

SB: So, the clip in question was at the start of the year – you hadn’t taught that class before. (For those who haven’t seen Testing Teachers yet, Will is trying to get a troubled student out from under a table, and does so in a gentle way.)

WL: That’s right, I have some deeply embedded routines in my class. At the start of the year, they just weren’t used to the routines of doing vocab at the beginning of each lesson, and then quiet reading or writing, or a bit of mindfulness practice to calm them down.

SB: So, you were in the establishment phase then? Building relationships and rapport?

WL: I was building relationships with the kids, making sure that they feel successful in my class. I’m a calm teacher, kids say things to me that don’t really bother me, I’m not going yell at them. Once kids realise I’m not going to get angry with them, they settle down. I like kids to feel as safe and comfortable as possible in the classroom.

SB: “Indigenous kids are, on average, six times more likely to be below national standards than their non-Indigenous peers.” In your opinion, why is this so?

WL: It’s a complex issue. One of the things that does a disservice, people think there’s a silver bullet; broad sweeping policies for all Indigenous students that don’t address needs for all. In one of my classes, I had nine different language groups; there’s incredible diversity within Indigenous Australia. Indigenous diversity is so undervalued in Australia.

With my year ten class, we mapped their cultures onto a photo of the Indigenous Map of Australia. Students in only one class were affiliated with 17 different culture/language group – though most of them had numerous responsibilities and affiliations through different family lines.

SB: And you said the differences are not isolated to language, right?

WL: Absolutely, even within the Tennant Creek community, there are cultural ceremonial differences, kinship difference, totem differences. It’s all relative as well. Tennant Creek is a unique place and would be different to an Indigenous community in Western Australia or South Australia. They’re all so different.

Speaking on national standards for a moment, it doesn’t surprise me when a program works well in Northern Queensland, but then doesn’t in South Australia; people are so different. Lumping them all in is counterproductive.

SB: Would you say it’s a good case for groups determining their own approaches to improving educational outcomes?

WL: Absolutely, I think that’s what Tennant Creek are doing so well. They are upholding best practice, and trying new things. The principal there, Maisie Floyd is doing an incredible job at negotiating what’s best for the kids, and it’s locally contextualised for those students.

SB: what do you see as the most important ways to ‘close the gap’ in education – at a government level, for school leaders and for individuals working with Indigenous students?

WL: Those three levels all have a responsibility, but in different capacities. A collective contribution at each level speaks well to something I discovered in my history class – that’s having explicit learning about reconciliation.

To have students fit themselves into that narrative, and see where they are now and where they’ve come from, I found to be effective. They could see ‘oh wow, it’s incredible that we’re at school, and we’re doing really well’.

This ties in with TFA’s broader mission of empowering leaders in the classroom. Their hope is to inspire students in schools where students experience disadvantage. In the case of Tennant Creek, these leaders could return after their studies and effect change in their own communities.

That’s important for governments who are making the policies, but talking about race; culture and history is so important, especially in the context of Tennant Creek.

SB: Are you saying we need to get rid of the elephant in the room and explicitly teach our racial history in Australia?

WL: Possibly, but using narrative and open dialogue in a positive way. ‘This is the past; however, you are the people that can change that, this is how things have been done in the past, but you can make Australia a better place.’

Q: What would you say about the role of both-ways education in Indigenous education? Did you employ any examples of it?

I had a couple Indigenous mentors – Elders – if I developed curriculum I would run it by them first. They also introduced me to contacts in the community, people came to speak to the class. Kids in Tennant Creek live in two worlds, they have a rich cultural life and then their life in our education system. School is where they intersect.

SB: If you controlled government funding, what would those kids get?

WL: Well, they’d get great facilities, access to VET programs, but really, in my view, it’s not just about funding – you’ve just got to have the right people. In these contexts, Indigenous educators should be the aim. You want community members studying and coming back to community to teach. It’s about finding ways to bridge the two worlds and encourage students to return to Country after being out there working within the dominant system.

SB: Are you using what you learnt in your new posting in Sydney at Waranara Centre (which has a 30 percent Indigenous population)?

WL: I’m using my experiences, sure, but these kids are different, city kids, they’re not in the middle of the desert. I hope I can use some of the strategies, but I’m just building trust now. You need to get to know the kids really well before you can do this stuff. There needs to be mutual trust to establish your legitimacy. They can’t gauge your authenticity straight off.

SB: Finally, Indigenous cultures have a lot of strengths – how can educators build on these when working with Indigenous students?

WL: That’s right. I realised through teaching Indigenous histories and narratives, that there is incredible resilience and courage in these ‘against the odds’ stories. They’re inspirational, and you see the same in the kids. You meet these students who live so far from everything, come to school most days – so strong willed. I think acknowledging past has given them strength and resilience. These qualities can be built on as a way forward for the entire country.